NEW DELHI: In Delhi’s dynamic educational landscape, where gleaming private schools often symbolise success and privilege, a stark contrast exists for students from economically weaker sections (EWS). In some cases, these students have to frequently navigate a system fraught with subtle yet profound discrimination, which can deeply affect their academic experience and self-worth.As one parent recounts, a teacher was overheard telling a student in front of the whole class, “aap toh EWS wale hain (you seem to be from the EWS category)”.

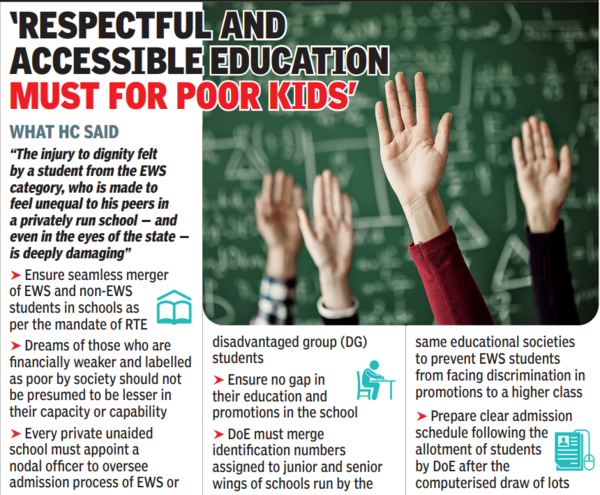

Recognising the gravity of these issues, Delhi High Court recently stepped in to address the imbalances faced by such students. “The injury to dignity felt by a student from the EWS category, who is made to feel unequal to his peers in a privately run school, and even in the eyes of the state, is deeply damaging,” Justice Swarana Kanta Sharma observed, while issuing a series of directions, including the appointment of a nodal officer, intended to make education “respectful and accessible” for underprivileged students.

Take the story of Deepa (name changed), an ambitious 16-year-old from a modest background. Her father, Ravi, recounts the challenges faced over the years after she joined a private school in west Delhi under the EWS category. They live in a JJ colony nearby. “The entry itself was a significant obstacle, requiring considerable effort and time to overcome. Once she got admitted, for many years, it was just subtle issues that I had to tackle. But soon enough, I could clearly see how different things were for her compared with other children.”

Ravi adds, “Some teachers would always speak in English over the phone. If I asked them to switch to Hindi, they would hang up.”

Things took a turn for the worse when Deepa got a compartment in her Class X exams. “At first, the school didn’t give her a chance to clear the compartment. They kept telling me to enrol her in another school. After much effort, when she finally got the opportunity to sit for the exam and passed it, they still didn’t let her return to school. For four months, my daughter had to stay at home. This did not happen with regular students who got a compartment,” says Ravi, who works as a labourer earning Rs 8,000 a month.

The aggrieved father had to turn to the court for assistance, which led to a notice being issued to the school. Only then was Deepa, now in Class XI, able to return to her classes. However, the challenges didn’t stop there. “In the beginning, they provided free books and uniforms. Now, they have discontinued it and insist that we purchase everything from the school. I had to pay Rs 800 for a T-shirt that I could buy for Rs 150 outside,” he says.

Ravi’s sentiments echo a broader issue that many EWS students may be facing: the sense of being perceived as inferior.

Ashok Agarwal, a lawyer dedicated to advancing children’s education and ensuring the effective execution of Right to Education (RTE) Act, acknowledges the existence of discrimination from the outset. However, he notes that after constant efforts from various quarters, the situation appears to have improved over time. “After HC issued orders on Jan 10, 2004, in response to a PIL filed by NGO Social Jurist, private schools built on govt land in Delhi began admitting EWS students. In the beginning, the schools opposed it, even tried to instigate parents who were paying fees to resist EWS admissions,” he says.

For these kids, if getting admission was a significant challenge, navigating the school environment proved even more difficult. Agarwal adds, “Schools then started discriminatory practices against EWS students. They were not allowed to sit with other students, were asked to wear a differently coloured uniform, made to attend separate classes, ‘W’ was written on their nameplates that meant ‘weaker section’. They were humiliated. However, after protests and court intervention, things improved over the years. The recent HC judgment is a landmark decision to further the cause of inclusive education.”

For many families, the EWS quota was a crucial opportunity to secure quality education for their children. Sunita and her husband were elated when their daughter, Himanshi, now in Class IX, got admitted to a private school in Ashok Vihar. “We chose to utilise the EWS quota to enrol her in a private school because, at that time, govt schools didn’t offer quality education. They claimed to teach English, but often teachers were absent, and in many cases, the teachers themselves didn’t know the language. We wanted Himanshi to receive the best education we could provide,” explains Sunita. Her husband works as an electrician.

Although Himanshi has not been directly targeted or discriminated against in her class, Sunita is aware of the biases EWS students face within the school environment. “I have heard that some teachers pass remarks like jhuggi jhopdi se hai (they come from a slum) when referring to EWS students, even in front of the whole class,” she says.

Another parent, speaking on the condition of anonymity, shares, “When I had to admit my son in nursery class, I went to at least nine schools. They kept delaying my application and kept asking for more and more documents. Years later, my son, now in Class VIII, clearly knows that he got admission through the EWS quota. Who told him? If there was no discrimination, why would this even come up. There is a clear divide. It’s not just about what’s provided but also about how our children are made to feel.”

The high court’s ruling offers a glimmer of hope for many families. Ravi expresses cautious optimism: “The court’s decision is a step in the right direction. We hope it will foster a more inclusive environment where our children can thrive. My daughter has only one year left in school, but I hope this change benefits all future students.”