Chennai residents were once again reminded of their city’s vulnerability last month, as Northern Tamil Nadu battled heavy rains that left streets waterlogged, homes damaged, and lives disrupted. The remnants of Cyclonic Storm Ditwah over the Bay of Bengal brought downpours, submerging several areas of Chennai and its northern districts. Residents waded through knee-deep water, facing a reality many hoped was behind them.Authorities confirmed four deaths in rain-related incidents, while thousands of homes and acres of standing crops were destroyed. For a city that has seen some of its worst floods in recent history, the question now is whether Chennai is truly better prepared for the next deluge.

Stormwater Drains: Progress And LimitationsFrom 2021 to 2025, the Greater Chennai Corporation (GCC) undertook a massive initiative to improve the city’s drainage network. Over this period, the GCC laid 1,144.5 km of stormwater drains, spending approximately Rs 5,000 crore, with 74% of the works completed by mid-2025.A flagship Asian Development Bank–backed project in the Kosasthalaiyar basin alone accounts for 641 km of integrated drains in North Chennai, costing an estimated Rs 3,059 crore.Yet, experts caution that even this scale of construction is insufficient. While drains have been laid across the city, flooding continues because major canals and rivers remain desilted, and thousands of encroachments obstruct the free flow of water.The Buckingham Canal, for instance, is encroached in multiple sections in Mylapore and Chepauk. This canal is a critical artery, channeling water from the sea to the Kosasthalaiyar, Cooum, and Adyar rivers. Each of these rivers also suffers from encroachments, with over 1,000 illegal structures reported in each. Over the past two years, the GCC has relied on high-powered pumps to remove water when stormwater drains failed, highlighting the limitations of the current system.

Brimming Kosasthalaiyar Floods Encroached Localities In North ChennaiNorth Chennai neighborhoods received nearly double the rainfall compared to other parts of the city, but encroachments along the Kosasthalaiyar River left residents especially vulnerable.At the river’s confluence with the Puzhal surplus channel and Buckingham Canal in Ennore, the absence of boundary walls allowed water to breach side walls, inundating local encroachments. Many residents were forced to vacate homes and seek refuge in community halls.Traffic snarled in areas like Retteri as third lanes and service lanes turned slushy, pushing commuters to the right-most lane. The GCC closed at least four stormwater drain outlets along Buckingham Canal at Tondiarpet, Kodungaiyur, and Kargil Nagar to prevent reverse flow during the flooding.

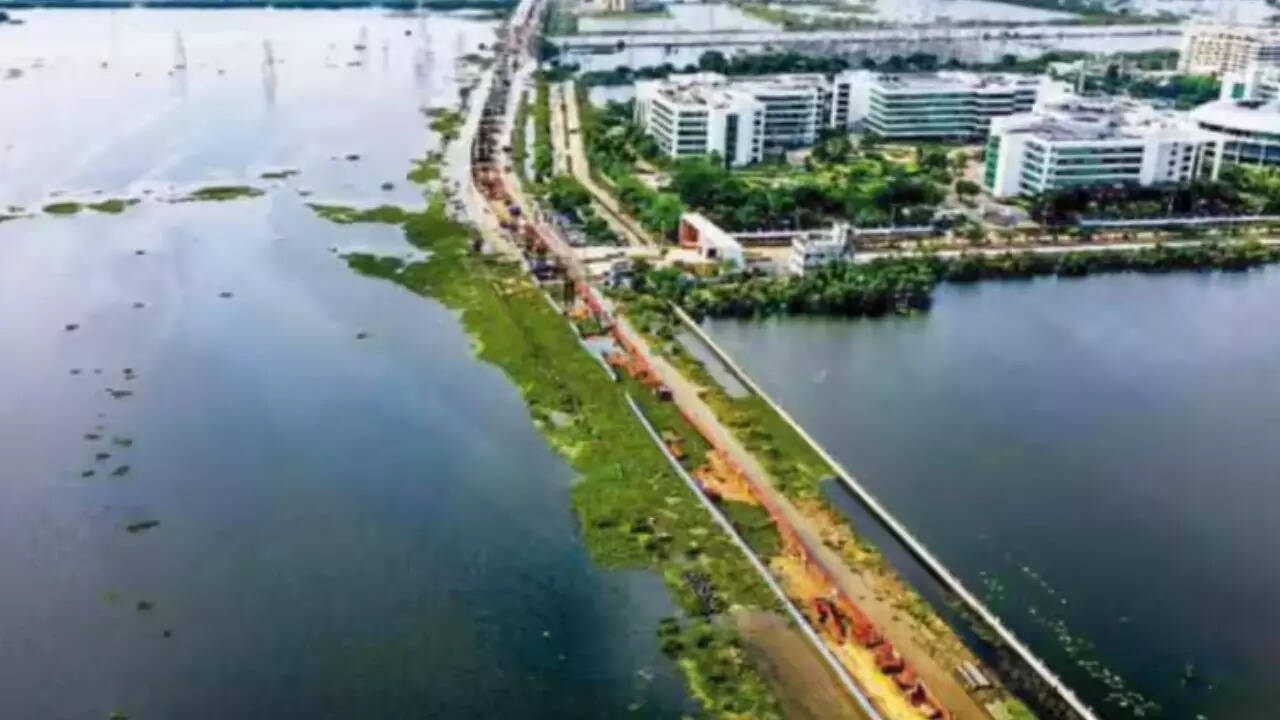

NGT Halts Construction Around Pallikaranai Marsh To Curb FloodsThe National Green Tribunal (NGT) recently halted all planning permissions and construction approvals in and around the Pallikaranai Marsh, Chennai’s last surviving wetland, providing an opportunity for its revival.The tribunal directed all stakeholders — CMDA, GCC, the environment department, and the state wetland authority — to freeze building approvals until the marsh’s boundaries and buffer zones are scientifically mapped and integrated into the city’s master plan.A recent mapping exercise by the Tamil Nadu Wetland Mission found that over 40% of the 21.25 sq km marshland is encroached, with 8.66 sq km of its area under illegal occupation. The NGT emphasized the importance of the marsh for flood prevention, noting that 50 stormwater inlets discharge directly into it.Water from upstream lakes in Pallavaram, Keelkattalai, and Narayanapuram flows into the marsh, along with water from south Chennai through OMR. Experts suggest reclaiming bio-mined areas and deepening them to store more water, as recommended by Anna University, which identified a 100-acre dump yard for potential water storage. Currently, this land is at surface level and underutilized.Ennore Creek And Kosasthalaiyar: Encroachment And RiskIn North Chennai, Ennore Creek and Kosasthalaiyar wetlands present a similar story. A 2020 report by the Save Ennore Creek campaign documented 667 acres of backwaters encroached by public sector undertakings after the 2015 floods. Other estimates suggest that over 1,000 acres of the 8,000-acre creek system are encroached, and fly ash from thermal power plants has reduced water depth in many channels.Flood Risk Along Tamil Nadu’s CoastA recent study warns that flood risk along Tamil Nadu’s coast, extending up to 25 km inland, including Chennai, will intensify due to unchecked urban growth, land use changes, and erratic rainfall triggered by climate change.The study highlights Chennai, Cuddalore, Nagapattinam, Puducherry, Chengalpet, and Kancheepuram as both low-lying and high-risk zones. Under future climate scenarios, particularly SSP370 and SSP585 representing moderate and high emissions, these districts are projected to shift to very high flood susceptibility zones, threatening millions and key infrastructure.Using satellite data, machine learning, and climate projections, the study found that sprawling construction, loss of water bodies, and rising rainfall will worsen flooding, especially during the northeast monsoon. In extreme scenarios like SSP585, average annual rainfall may exceed 5,600 mm by 2100, while land use changes show increased settlements and declining forest cover, compounding flood exposure.The study recommends creating flood maps to guide development and prevent encroachment into vulnerable zones.

Chennai to Face Unavoidable Floods and Droughts, Warns IIT-M ExpertChennai cannot fully escape the twin challenges of floods and droughts, says Balaji Narasimhan, professor in the Department of Civil Engineering at IIT-Madras, who collaborates with the government on low-impact development (LID) measures and sustainable drainage systems (SuDS) to enhance urban water security.Narasimhan highlighted that a slightly above-normal northeast monsoon is forecast for Chennai. According to the IMD’s seasonal forecast, there is a 60% probability that rainfall from October to December over peninsular India will be about 12% above normal. Combined with already above-normal southwest monsoon rains, saturated soil, and full water bodies, the flood risk in the city is expected to rise.He further explained that Chennai’s water supply and sewerage are managed by the CMWSSB, while the Greater Chennai Corporation (GCC) oversees stormwater drainage and solid waste disposal. This division creates gaps and conflicts in infrastructure construction, operation, and maintenance, leading to inefficiencies, sewage and solid waste issues, water body pollution, and inadequate flood disposal capacity.According to Narasimhan, consolidating these responsibilities under a single agency—either GCC or CMWSSB—would allow for integrated, more efficient planning and management of water supply, drainage, and sewage systems.He also emphasized the need for a comprehensive approach that incorporates blue-green infrastructure, going beyond traditional rainwater harvesting. This would complement existing grey infrastructure, such as stormwater drains, to help flood- and drought-proof Chennai.He futhur stated that A drainage master plan, along with a flood ‘hazard–risk–vulnerability and capacity assessment’ (HRVCA) for Chennai is the first step. Based on this, the govt needs to chart out a series of projects over many years to reduce the risk and vulnerability. Such a plan would give room for our waterways and water bodies, recharge our aquifers, and thus improve our resilience against floods and drought.He further stated that a drainage master plan, along with a flood ‘hazard–risk–vulnerability and capacity assessment’ (HRVCA) for Chennai, is the first step to improving flood resilience. Based on this, the government needs to chart out a series of long-term projects to reduce risk and vulnerability. Such a plan would provide space for waterways and water bodies, recharge aquifers, and enhance the city’s resilience against floods and droughts.

Rs 42 Crore Project To Keep Perumbakkam Flood-FreeThe highways department is executing a stormwater diversion project near Elcot, costing Rs 42 crore, to ensure Perumbakkam and surrounding areas off OMR remain flood-free.A 1.7 km twin-cell culvert is being built to carry rainwater from Perumbakkam Marsh to Buckingham Canal.A low-level bridge, which previously caused frequent inundation, is being replaced with a high-level bridge.Officials are also desilting drains on Perumbakkam Main Road.The water resources department is widening Okkiyam Maduvu at Rs 27 crore, while CMRL is constructing two high-level bridges to improve flow.Local commuters report that existing drainage systems failed even under moderate rainfall, highlighting the urgency of completing these projects.2015 Flood: Role Of Traditional Tanks In Mitigating FloodsChennai’s worst flood occurred on December 1, 2015, when 50 cm of rainfall, combined with water released from the Chembarambakkam Reservoir, submerged the city.Studies now suggest that if upstream water bodies, which currently store 174.7 million cubic meters, are lost to urbanization, flood damages could increase by 44%, deaths by 60%, and population risk by 40.5% in a similar scenario.Research by GFZ Potsdam, IIT Roorkee, and IIT Madras, published in Urban Climate, found that retaining traditional tanks could have reduced flood losses by 17%, fatalities by 12%, and flood levels by up to 0.8 meters in neighborhoods like T Nagar, Ashok Nagar, and Virugambakkam.Activists Highlight Underreporting Of DeathsActivist A Narayanan points out that government figures understate the human cost: “The official figure of 347 deaths in 2015 cannot be accepted. Ambulances simply could not move during the floods.”Political Disputes Over FloodsFlood management has also been a political flashpoint. Last year, DMK and AIADMK debated the 2015 floods in the state assembly. CM M K Stalin argued that unannounced water release from Chembarambakkam Lake caused fatalities . AIADMK leader Edappadi K Palaniswami contended that the Adyar River’s capacity was sufficient, and flooding resulted from excess rain and water from over 100 downstream lakes.

Experts’ View: Lessons From The 2015 FloodResearchers say Chennai’s 2015 flood could have been less severe if the city’s traditional rainwater-storing tanks had been intact. Flood losses could have dropped by 17% and fatalities by 12%, with water levels reducing by up to 0.8 m in areas like T Nagar, Ashok Nagar, Virugambakkam, and Saidapet. The population at risk would have fallen by 25.3%.Abinesh Ganapathy noted that while the Chembarambakkam reservoir’s release contributed, it accounted for only 25% of upstream flow. “Water bodies act as buffers, reducing inflow into the Adyar River. Lost lakes could have moderated flooding further,” he said.Simulations showed that if traditional tanks existed, flooding in lower-risk zones like Vadapalani, Mylapore, Alwarpet, Adyar, Ashok Nagar, Ekkattuthangal, and Guindy could have dropped 23–37%, rising to over 60% in parts of Vadapalani, Mylapore, and Alwarpet when encroached tank areas are included. Conversely, if upstream tanks were also lost, high-risk areas like Koyambedu, Adyar, Porur, T Nagar, Nandanam, St Thomas Mount, Mylapore, RA Puram, and Nungambakkam would see flooding expand by 45–54%.T Kanthimathinathan, coordinator of the Tamil Nadu State Disaster Management Authority, emphasized that the key to reducing Chennai’s flooding lies in preserving and protecting the flow paths of existing water bodies to downstream systems amid urbanization. He noted that between 1975 and 2008, the city lost many water bodies due to expansion, including those in Nungambakkam, Mambalam, and Mogappair, leaving only 49 significantly shrunk water bodies intact today.Understanding Modern Flood Risks Experts warn that flooding today is driven not just by total rainfall but by short, intense downpours that the land cannot drain quickly. Rising atmospheric moisture is increasing the vertical spread of clouds, making future storms more severe and floods more aggressive.A recent study highlights elevation, rainfall, and land cover type as the most critical factors influencing flood risk. In Chennai, extensive construction and the loss of natural drainage have worsened flooding, particularly during the northeast monsoon.“Flooding today isn’t just about more rain, it’s about intense downpours in short bursts, and the land simply can’t empty the water fast enough. The vertical spread of clouds is increasing due to rising atmospheric moisture, making future storms even more aggressive,” said M V Ramana Murthy, former director of the National Centre for Coastal Research.Led by the National Institute of Technology, Trichy, and published in Geoscience Letters, the study used satellite data, machine learning, and future climate projections to map flood-prone zones along the Tamil Nadu coast under four emission scenarios. Chennai faces rising flood risk due to the shrinking of water bodies such as Pulicat, Puzhal, and Chembarambakkam.

Chennai’s Persistent Flood Vulnerability Despite Infrastructure UpgradesChennai has experienced five major floods between 1943 and 2005, with 1943, 1978, and 2005 particularly severe. Rapid urbanization, often illegal, has led to the loss of wetlands and natural sinks, while aging infrastructure and poorly designed drainage have increased the frequency of severe flooding.Despite multi-crore drainage projects and restoration efforts, Chennai remains highly vulnerable to floods. Factors such as encroachment, loss of wetlands, uncoordinated infrastructure management, and climate change–induced rainfall make it clear that structural and policy reforms are essential.Experts argue that only integrated planning, combining grey and blue-green infrastructure, protection of existing water bodies, and climate-sensitive urban development, can reduce flood risk. Without these measures, Chennai may continue to face recurring floods, even as millions hope the city has finally learned from its past disasters.