At 6.30 am in a gated community off Varthur Road in Bengaluru, the day begins not with birdsong or early traffic, but with the piercing reverse beep of a water tanker easing into the driveway. Residents wearing shorts and T-shirts lean over balconies, checking if the blue-and-white lorry carries the logo they now trust more than any brand of bottled water: Sanchari Cauvery – BWSSB.For many Bengalureans, this has become the first ritual of summer — not turning on a dependable tap, but waiting for a water tanker to arrive on schedule. On paper, Sanchari Cauvery, the Bangalore Water Supply and Sewerage Board’s (BWSSB) state-run tanker service, is projected as a success.

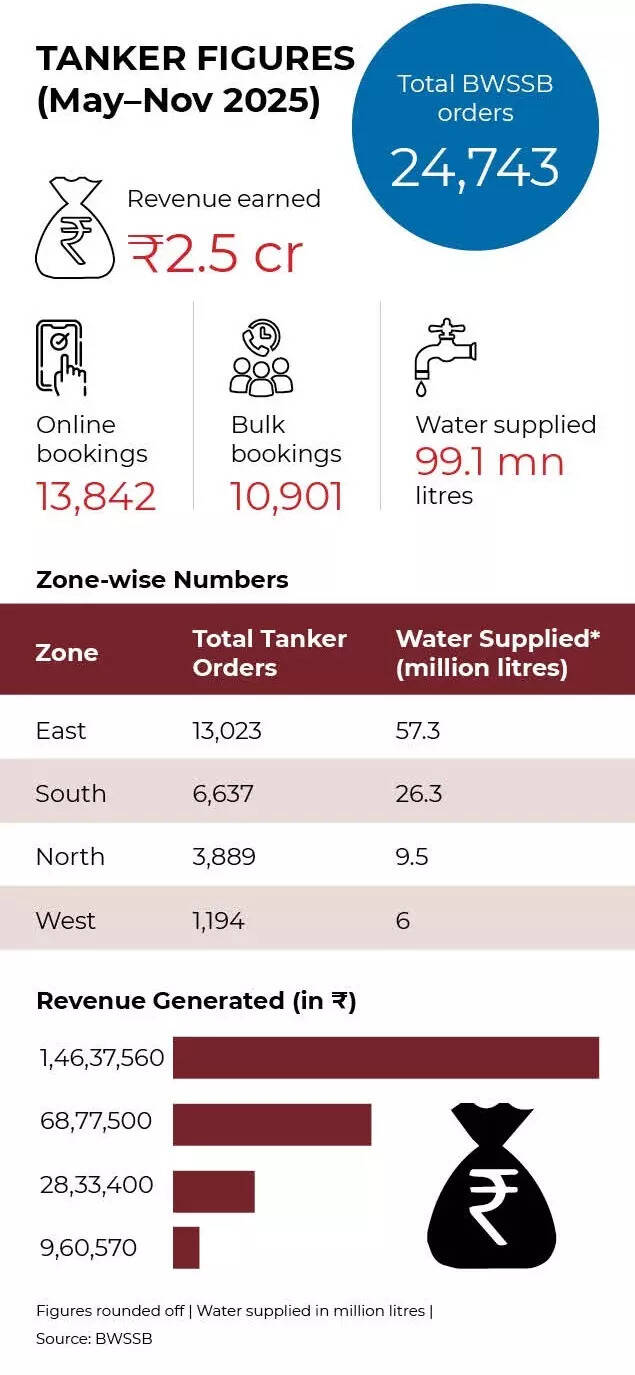

In just six months between May 9 and November 20, 2025, the board logged 24,743 tanker bookings, deploying 250 branded vehicles at fixed rates and earning about Rs 2.5 crore in revenue. Nearly 14,000 of those bookings were placed online. Prices — Rs 660 for 4,000 litres — undercut the private market and brought a degree of predictability to a notoriously business.

But beyond the reassuring blue-and-white branding, a harder question looms: Is Bengaluru quietly normalising permanent tanker dependence instead of fixing its broken water system?A city built on water, now running dryLong before tankers and pipelines, Bengaluru was shaped by water. Until 1896, lakes and wells were the city’s primary sources, before piped supply arrived from Hesaraghatta. These water bodies — locally called tanks — were not ornamental lakes but carefully engineered earthen dams built across valleys to irrigate paddy fields downstream. All were interconnected, forming a cascading hydrological network that fed three major valleys.

At its peak, Bengaluru had close to 1,000 such tanks.

Centuries later, that system lies in ruins. In a 2013 paper titled ‘Death of lakes and future of Bangalore’, retired bureaucrat V Balasubramanian concluded that the city’s lakes now largely store “sewage wastewater”.The evidence is visible everywhere. Of the nearly 800 lakes in the BBMP and Bengaluru Urban district areas, 125 have gone completely dry last summer, with 25 more on the brink. Of these, 100 are in Bengaluru Urban district and 25 within BBMP limits.Some dry lakebeds have overnight become cricket pitches for neighbourhood boys. Others lie cracked and dusty, silent markers of an ecological collapse.BBMP has custody of 184 lakes; 50 of them are in dire straits. Beyond BBMP limits, Bengaluru Urban district has over 600 lakes, nearly 100 of which dried up this year alone.There are bright spots, officials insist. Six lakes in Bengaluru Urban district are full and 19 are between 50% and 90% capacity — largely due to the Koramangala–Challaghatta and Hebbal–Nagavara valley projects. But such examples remain exceptions.Nallurahalli Lake near Whitefield and Vibhutipura Lake near HAL have turned into playgrounds. Sankey Tank, in the heart of the city, is among those drying rapidly. At least 15 lakes are now being artificially filled with treated sewage water by BWSSB; those far from treatment plants must wait for rain.A city growing faster than its pipesBengaluru’s water crisis is inseparable from its growth.According to the Directorate of Economics and Statistics, the city’s population is projected to rise from around 1.22 crore in 2021 to nearly 1.47 crore by 2031 — a more than 20% jump. Its share of Karnataka’s population will rise from 18.2% to 20.7% in a decade.“Bengaluru’s growth is largely driven by livelihood opportunities,” said K Narasimha Phani, joint director at DES, noting that migration — from within and outside the state — fuels the expansion.But planning has not kept pace. “Bengaluru’s town planning framework is very old,” said Dr S Madheswaran, adviser to Jain University and former ISEC director. Peri-urban areas absorbed into the city remain blind spots, falling through governance cracks and missing basic services.The result is a city that sprawls faster than its water infrastructure.From tanker mafia to state-run trucksWhen piped water and borewells fail, tankers fill the gap.During the failed monsoon of early 2024, nearly half of Bengaluru’s 13,900 borewells ran dry. Private tanker prices surged from a few hundred rupees to as much as Rs 3,000 per load. The state had to commandeer irrigation and commercial borewells just to keep neighbourhoods supplied.BWSSB data shows how fragile this backup remains. Of 11,816 public borewells, 2,035 have already dried up and another 3,700 yield “very little” water — nearly half effectively non-functional.

Sanchari Cauvery was born out of this emergency. Launched by deputy chief minister DK Shivakumar in May 2025, it promised BIS-certified Cauvery water delivered by GPS-tracked tankers at fixed prices. “We are supplying BWSSB-certified Cauvery water at reasonable prices… to ensure people don’t fall prey to exploitation,” he said.Residents have welcomed the price cap. Former Prime Minister HD Deve Gowda highlighted the burden in Parliament: “For a family of four, this translates to Rs 20,000 per month just for water.”Yet the geography of tanker demand reveals deep inequality. BWSSB data shows the East zone alone accounted for 13,023 bookings — more than half the city’s total — while the West zone placed just 1,194 orders. Bulk orders, mainly from apartment complexes and commercial users, made up 10,901 bookings.

Core neighbourhoods with legacy Cauvery connections cope better. Outer wards and newly merged villages — often home to premium gated communities — remain tanker-dependent. In a cruel inversion, wealthiest households live in the most precarious water landscapes.‘We plan our lives around water’In BTM Layout, Pallavi Jaghanath says her family receives tanker water once every three days. “Each load costs about Rs 1,000. By the end of the month, we are spending close to Rs 10,000 just on water,” she says. “And this is still not clean, continuous supply.”In Pattandur, Shrihari Vittal Rao, who manages water for a five-storey building with 20 flats, says tanker costs fluctuate sharply. “We spend Rs 20,000 to Rs 25,000 a month. In summer, operators increase prices by Rs 100 to Rs 150 per tanker. There is no option but to pay.”

In Kamadhenu Layout in Mahadevapura, residents say the situation has dragged on for over 18 months. Monthly water bills there touch Rs 35,000, forcing residents to ration water and defer routine activities.Rishabh Aditya, a software engineer living in East Bengaluru, describes the strain of uncertainty. “We have an infant at home. Tankers don’t arrive at fixed times. Sometimes we stay awake till 1am waiting. Water has become something you chase.”For senior citizens, the burden is financial as well as physical. “Depending on tankers every day is draining our savings,” says Jaishankar V, a retired resident. “For people living on pensions, Rs 20,000 a month for water is simply not sustainable.”

Politics of thirst?The tanker crisis has spilled into the legislature and election campaign also. MLAs across parties have demanded action against the “tanker mafia”. Deputy chief minister DK Shivakumar has announced mandatory tanker registration, price regulation and even government takeover of borewell-supplied tankers.According to Shivakumar, nearly 25% of Bengaluru’s population depends on tanker water. He has promised that Cauvery Stage V will address shortages in the 110 newly added villages, while unused allocations from the Cauvery basin — up to 6 tmc — will be redirected to the city.Opposition leaders, including BJP’s Arvind Bellad, have accused the government of failing to curb tanker dependence despite water availability, keeping the political spotlight firmly on Bengaluru’s taps — and trucks.During 2024 assembly election campaign, Prime Minister Narendra Modi also sharpened the attack, accusing the Congress government of mismanagement. “They have changed the tech city into a tanker city and left it to the water mafia,” he said, turning Bengaluru’s water crisis into a national talking point.A Deadline for cityThe warning signs are no longer coming only from activists or researchers — they are now being sounded by the city’s own water utility.In an internal assessment cited by The Times of India on June 9, the Bangalore Water Supply and Sewerage Board cautioned that Bengaluru could face an acute drinking water shortage as early as 2039 if current consumption patterns, groundwater depletion and delayed infrastructure upgrades continue.

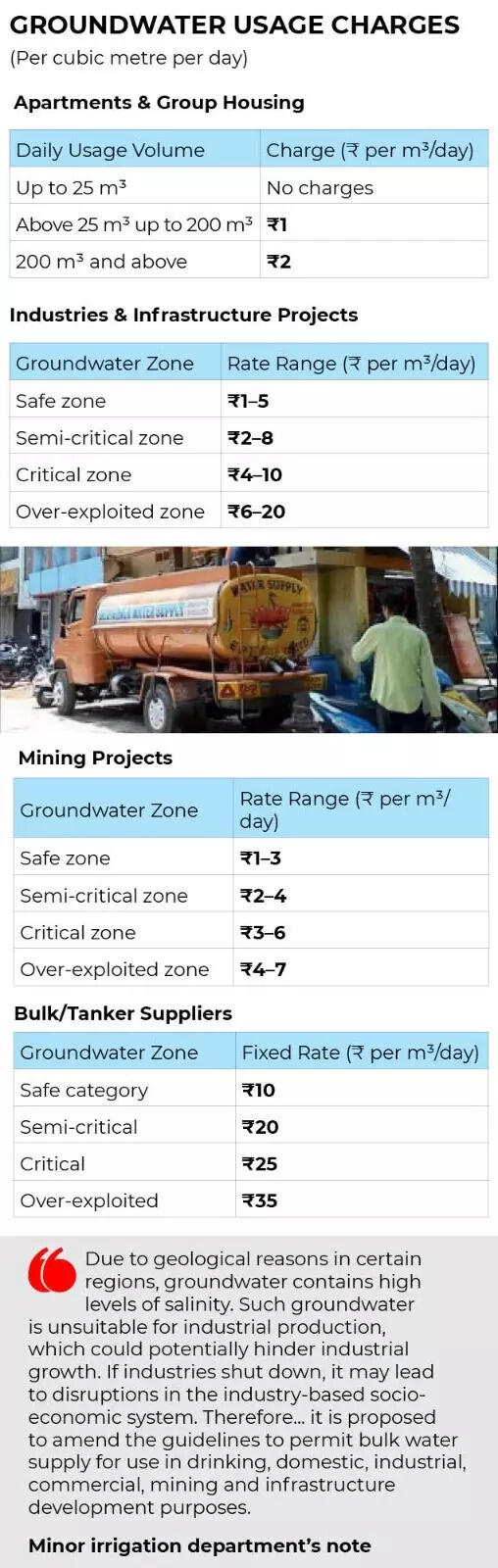

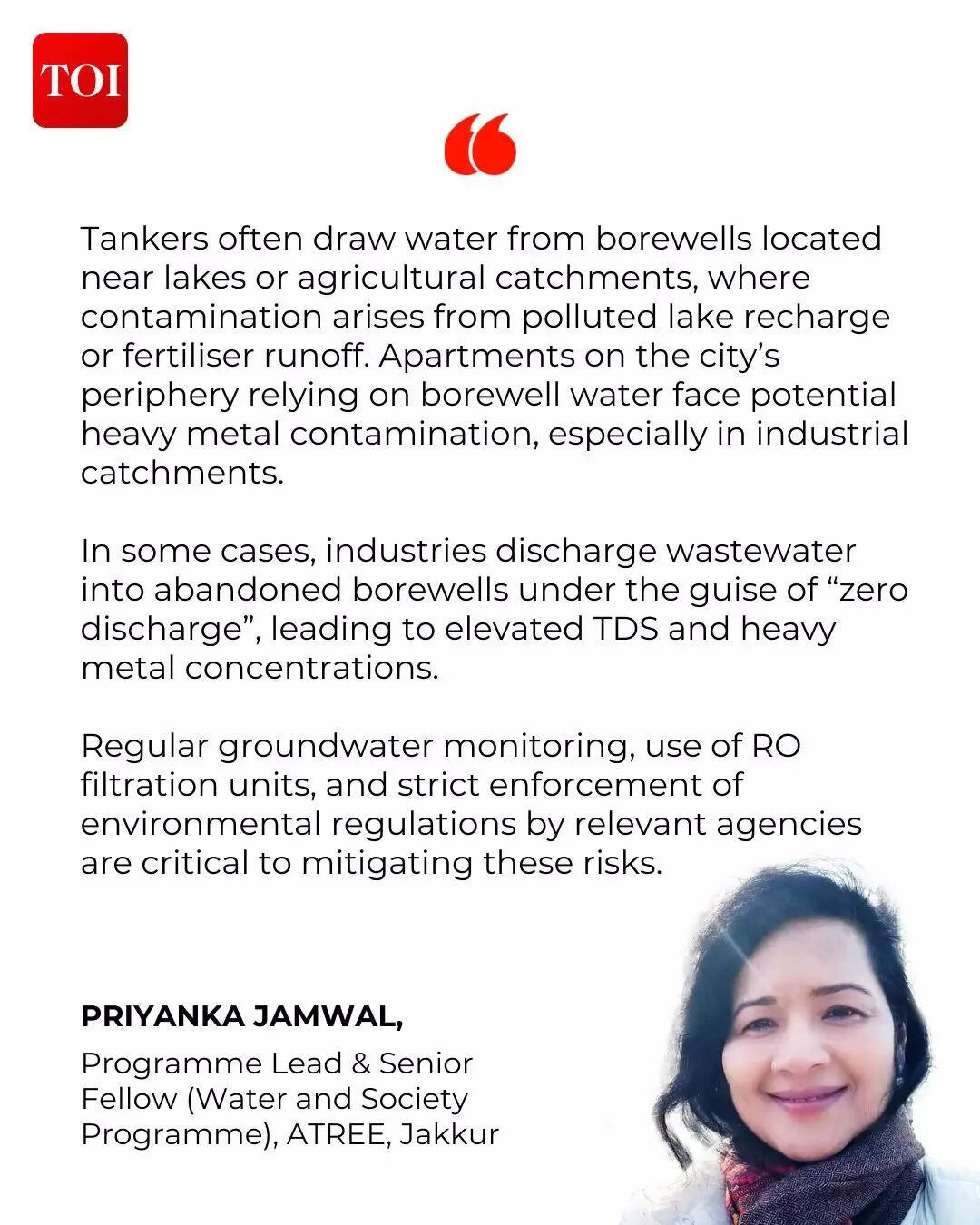

The report flags unchecked urban expansion, over-dependence on borewells, shrinking recharge zones and rising per capita demand as key drivers of the looming crisis.Water quality: the hidden emergencyScarcity is only part of the story. Quality is the other.Many apartments report foul-smelling tanker water with visible impurities. The desirable TDS limit for drinking water is under 500 ppm; residents report readings of 400–800 ppm, sometimes crossing 1,000 ppm in fringe areas where borewells exceed 900 feet.“Tanker water’s TDS levels are over 500 ppm,” says Neha Advani of Hillcrest, House of Hiranandani, where tanker and Cauvery water are mixed in the same tank. “If builders had created separate tanks for Cauvery water and connected those to kitchens, we would have needed only regular filters,” she says.

Across Bengaluru’s newer layouts, water systems designed for mixed-source supply are compounding the problem. Even where Cauvery water is available, it is often stored and distributed alongside borewell and tanker water, increasing hardness levels.This has pushed households toward multiple layers of purification — heavy-duty RO systems for drinking water and softeners for bathing — resulting in significant water wastage at a time when every drop counts.Medical professionals warn that the long-term health implications of poor water quality are being underestimated.

“If sewer lines run parallel to drinking water lines and are old or break at multiple points, contamination can occur,” says Dr Parvesh Kumar Jain, Professor and Head of Medical Gastroenterology at the Institute of Gastroenterology and Organ Transplant, Bengaluru. “When sewage mixes with drinking water, it causes bacterial and viral infections.”While infections such as E. coli, hepatitis A and hepatitis E are prevalent, pinpointing contamination sources remains difficult. Elevated fluoride and heavy metal levels pose chronic health risks, including bone toxicity, kidney damage, kidney stones, high blood pressure and heart disease.“Unlike microbial contamination, high TDS does not make water immediately infective,” Dr Jain explains. “But its long-term effects can be devastating. We need effective source detection, robust surveillance systems and better water supply infrastructure.”Shashank Palur, senior hydrologist at WELL Labs, warns of a deeper risk. Leaking sewer lines allow sewage to percolate into groundwater. “If sewer and water lines are damaged, sewage can enter water supply lines when pipes are empty,” he says, arguing for system-wide sewer overhaul.While scarcity dominates public discourse, experts warn that water quality is emerging as an equally dangerous, if less visible, crisis in Bengaluru’s tanker-dependent neighbourhoods.The government has been urged to implement comprehensive water testing protocols and invest in advanced filtration systems to mitigate the risks associated with elevated total dissolved solids (TDS) levels. Ensuring safe drinking water, specialists argue, must be treated as a public health priority, not merely a supply-side challenge.

Bengaluru Water Crisis

A commonly used treatment process — charcoal and sand filtration followed by chlorination — is effective in removing pathogens and suspended particles but does little to reduce TDS. Reverse osmosis (RO) filtration significantly lowers TDS levels, but also strips water of beneficial minerals and leads to substantial water wastage.In many apartment complexes, residents have been forced to create private, parallel purification systems. Siddharth Singh of Ahad Euphoria on Sarjapur Road, like many others, has installed water softening devices in bathrooms to prevent hair fall and skin dryness — a response driven less by luxury than by compulsion.Data tells a bleak storyIISc scientists have quantified what residents already feel. Over 50 years, Bengaluru’s built-up area has increased by 1,055%, while water spread area has fallen by 79% and vegetation by 88%.“The extent of water surface… has shrunk from 2,324 hectares in 1973 to just 696 hectares in 2023,” said Prof TV Ramachandra. “Of the remaining water bodies, 98% are encroached upon and 90% fed with untreated sewage or industrial effluents.”

ATREE’s study adds another layer: half the city’s households use less than 90 litres per capita per day, while the top 10% consume 342 lpcd. Inequality is built into the system.Beyond Bengaluru: a statewide emergencyWater stress is not confined to the capital. Protests erupted across Kalyana Karnataka, with farmers demanding releases from upstream reservoirs.In April this year, CM Siddaramaiah wrote to Maharashtra seeking water from Warna, Koyna and Ujjani reservoirs to meet drinking needs in northern districts.Even with reservoirs partially full, erratic rainfall and uneven distribution have raised fears of drinking water scarcity before the monsoon returns.When citizens stepped in — and were pushed outIf Bengaluru’s lakes have survived at all, much of the credit goes to citizen groups.Puttenahalli Puttakere Lake, once a sewage-filled wasteland, is today a thriving ecosystem. Butterflies migrating from the Western Ghats to the Eastern Ghats used it as a stopover earlier this year. Local residents now eagerly await their return before the northeast monsoon.The transformation was led by the Puttenahalli Neighbourhood Lake Improvement Trust (PNLIT), which converted the dump yard into what it proudly calls “a people’s lake” — while also acting as watchdogs against encroachment.“Encroachment in the lake premises is always a matter of concern,” says Usha Rajagopalan, chairperson of PNLIT.

Similar stories played out across the city. Mahadevapura Parisara Samrakshane Mattu Abhivrudhi Samiti (MAPSAS) maintained a chain of interconnected lakes — Kasavanahalli, Kaikondrahalli and Saul Kere — covering nearly 200 acres.But this citizen-led model came to an abrupt halt in 2025 after BBMP stopped renewing MoUs with lake trusts, citing a March 2020 high court order that barred MoUs with corporate entities for lake rejuvenation until legal clarity was obtained. BBMP extended the interpretation to citizen bodies as well, arguing that corporates may indirectly fund them.Citizen groups dispute this. “High Court stay is being misinterpreted to include citizen groups. The court order restraining corporates from maintaining lakes should not apply to us,” a MAPSAS trustee said, adding that MoUs were halted under instructions from the Karnataka Tank Conservation and Development Authority.Preeti Gehlot, special commissioner at BBMP, maintains the court order applies to all. She declined further comment.One unnamed BBMP official alleged that some citizen bodies profit from lake management. “A lot of these groups do not have expertise in lake management. They are taking away credit for what we have done,” he said.MAPSAS strongly rejects the charge. “We work pro bono. The volunteers seek neither name nor fame. The trustees take no remuneration. Our Trust records are professionally accounted and audited annually with no room for any misuse,” the trustee said.Even without MoUs, volunteers continue to act as watchdogs. “BBMP officers, often overworked and managing multiple lakes, rely on us for on-the-ground information,” he said.Citizen frustration is palpable. BBMP lacks funds and manpower for day-to-day maintenance, monitoring encroachments, buffer zone violations and sewage entry. Shilpi Sahu, a resident who has followed lake conservation for years, says, “Even if BBMP increases its workforce 10 or 20 times, they will not be able to match what the local community can do.”What a non-tanker future would requireEarlier this year, the Karnataka Groundwater Authority admitted in court that it operates with just 49 permanent staff and 30 outsourced workers against 440 sanctioned posts — an 82% vacancy rate. For all of Bengaluru, there are only two geologists.Officials described the authority as “functionally paralysed”.Instead of mapping aquifers or policing illegal borewells, enforcement is complaint-driven. “That means whichever neighbourhood shouts the loudest,” an official said.The consequences are visible in Whitefield, Mahadevapura and Devanahalli: borewells that once struck water at 300–400 feet now run dry at 1,200–1,800 feet. Tanker operators drill deeper in peri-urban villages to keep trucks moving.“When the referee is absent, every borewell owner is rationally selfish — and collectively suicidal,” one hydrologist observed.One practical solution lies underground.The Biome Trust has been working to recharge Bengaluru’s abandoned wells by partnering with the Mannu Vaddar community — traditional well diggers whose skills span generations. Since 2015, they have helped recharge nearly 2.5 lakh wells across neighbourhoods such as Yediyur, IIM Bangalore, Yelahanka, Cubbon Park, Lalbagh and Rainbow Drive.A typical recharge well, three feet wide and 20 feet deep, costs around Rs 40,000 and allows filtered rainwater to percolate into aquifers. Areas with such systems report reduced flooding and improving groundwater levels.The model has worked partly because Bengaluru already mandates rainwater harvesting. “This gave the Mannu Vaddars livelihood security and the city a partial solution,” the trust says — a reminder that water resilience may lie as much in traditional knowledge as in modern infrastructure.

Waiting for the tap to runAs summer approaches, anxiety rises. Some hope upcoming project phases will ease pressure. Others are less certain, having seen past assurances overtaken by growth.For now, Bengaluru continues to adapt — storing, rationing, adjusting. The city functions, offices open, traffic crawls, start-ups launch. But beneath the surface, an essential question lingers: how long can a modern metropolis depend on tankers to keep its taps running.Each successful delivery brings short-lived relief. Each empty sump brings the reminder back.But every blue-and-white tanker that pulls up at dawn is both a relief and a warning. It signals a city living beyond its hydrological means — one 4,000-litre booking at a time.If Bengaluru does not use this breathing space to revive its lakes, regulate its groundwater and fix its pipes, Sanchari Cauvery risks becoming not a stopgap, but a permanent crutch.(With inputs from Nithya Mandyam and Mini Thomas)