A Geographical Indication (GI) tag 15 years ago have placed chikankari embroidery in and around Lucknow today. Earlier this year, Naseem Bano, a Lucknow-based practitioner of Anokhi Chikankari, where the embroidery is invisible on the reverse side of the fabric, was conferred the Padma Shri.

But did you know that the delicate style originated in East Bengal, and travelled all over undivided India before settling down in Lucknow?

In the early 19th century, Madras Chikankari, along with that of Calcutta, Dhaka, Lucknow, Bhopal, Peshawar and Quetta, was described in detail in ‘Indian Art at Delhi 1903’, the official catalogue of the year-long public exhibition that was held as part of the Delhi Durbar to celebrate the coronation of King Edward VII from 1902-1903.

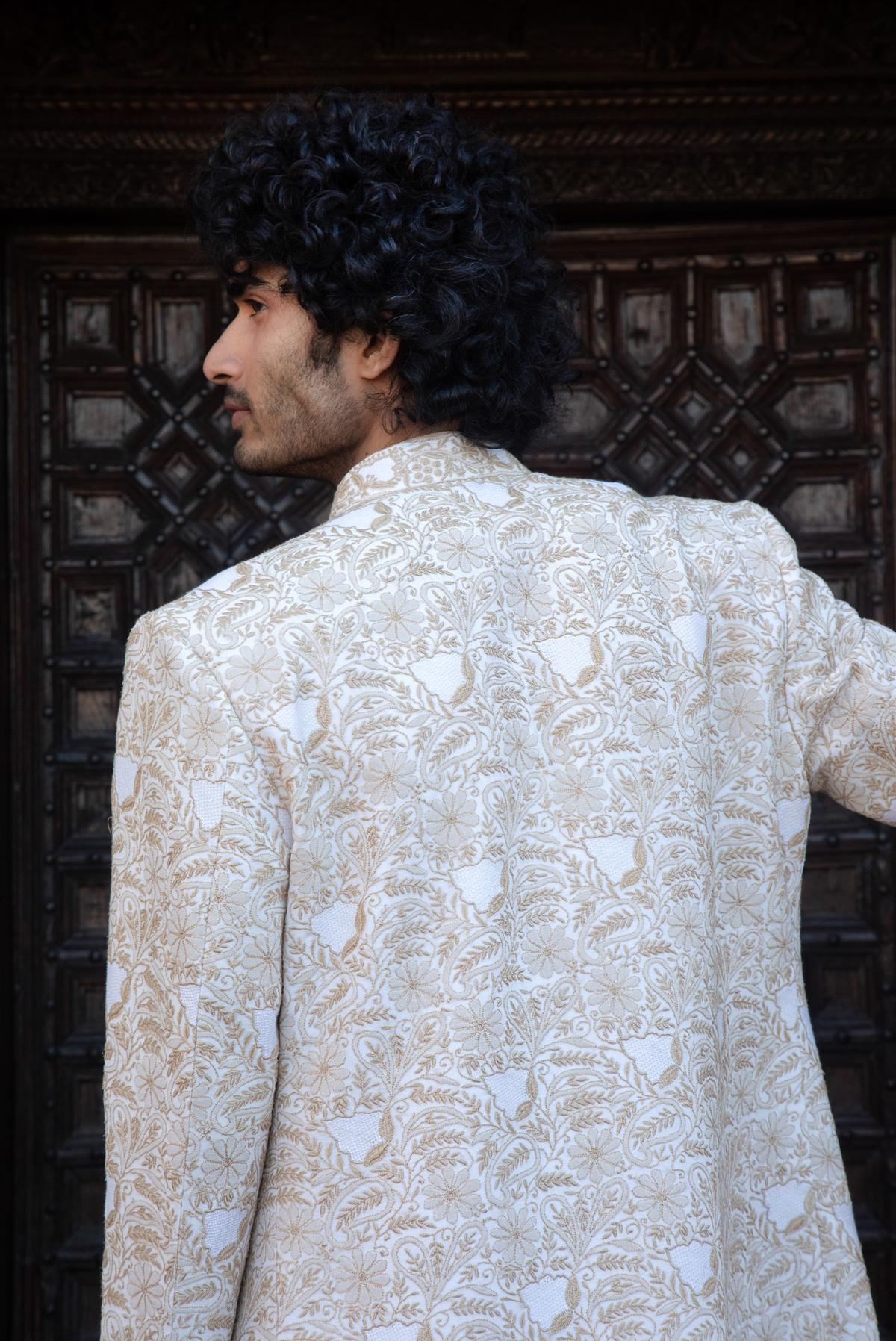

The process of creating Chikankari fabric.

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy: Anjul Bhandari

Written by Sir George Watt, a Scottish botanist who served as the director of the Delhi Exhibition besides other government positions, ‘Indian Art at Delhi’ was a valuable source of information on the country’s rich heritage of crafts, quite a few of which have faded away, due to changing tastes, and the industrial revolutions of succeeding years.

Chikankari (a Persian/Urdu coinage indicating needle as a metaphor) is known for its thread work done on diaphanous and breathable fabrics, and is thought to have been brought to the Indian subcontinent by noble families of Iranian descent in the Mughal court. It is considered to be the oldest form of indigenous embroidery in India.

Women Chikan embroiderers at work.

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy: Anjul Bhandari

Watt, in his book writes, “in historic sequence, it is probable that the craft originated in Eastern Bengal and was only carried to Lucknow during the period of luxury and extravagance that characterised the latter term of the Court of Awadh. The Kings of Oudh attracted to their capital many of the famous craftsmen of India, hence Lucknow, to this day, has a larger range of artistic workers than are to be found in almost any other town of India.”

Lucknow-based designer Anjul Bhandari whose eponymous couture label supports over 2,000 women Chikan embroiderers in and around the city, says that folklore claims that Nur Jahan, the daughter of a Persian nobleman in Murshidabad, was very fond of the craft besides being a skilled needlewoman. “Since the summers were very warm here, Chikankari was done on the finest mulmul fabrics, to please her,” she says.

Madras Chikankari, was described in detail in ‘Indian Art at Delhi 1903’, the official catalogue of the year-long public exhibition that was held from 1902-1903 as part of the Delhi Durbar to celebrate the coronation of King Edward VII.

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy: Paola Manfredi

Madras Chikankari

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy: Paola Manfredi

Chikankari began as a form of embroidery done on white washing material such as calico, muslin, linen or silk. Ordinary satin stitch was combined with a kind of button-holing technique, used to create white on white designs on garments, furnishings and linen.

Watt also lists out descriptions of 32 stitches that were used by craftsmen of yore.

“When fast fashion came in, we lost karigars (artisans), and the finesse that they had honed over the years,” says Anjul.

As royal patronage vanished, Chikankari evolved from being a male-dominated trade into a home-based cottage industry led by women artisans.

“It is a home-to-home craft. I may have to go down to two or three villages to get work done on a single garment. For instance, Kakori, is known for the finest version of a stitch called the ‘Murri’ (shaped like rice), while in Malihabad, the ‘Phanda’ (millet) stitch is famous. Encouraging the craftsmen in the villages around Lucknow, has helped us to revive nearly 18-20 stitches of Chikankari from oblivion,” says Anjul.

The thread test

As royal patronage vanished, Chikankari evolved from being a male-dominated trade into a home-based cottage industry led by women artisans.

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy: Anjul Bhandari

There are several stages integral to creating a fabric with Chikankari embroidery. Hand-drawn sketches of designs are used to create wooden blocks for printing. Specialist printers use the indigo-dyed blocks to lay out the design on white material.

“This is the only language that the embroiderer understands. If the printer misses something, the embroiderer will not be able to work,” says Anjul.

In the olden days, blocks used to be very small, and a printer would mix different kinds to make a whole jaal (net or grid) of taakas (stitches).

‘Jaali’ making artisans take over once the basic embroidery is done, creating meshes within the warp and weft of the base fabric. This is followed by dhulai (hand-washing) in the Gomti river, and then dyeing.

Common motifs include the paisley, paan’ (heart-shaped betel leaf), kairi (unripe mango), trailing vines and other floral patterns. Coloured fabrics were gradually incorporated to cater to modern tastes.

There are several stages integral to creating a fabric with Chikankari embroidery.

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy: Anjul Bhandari

“With over 10,000 shops thriving on Chikankari sales in Lucknow, connoisseurs have to look hard to find an authentic piece,” says Anjul. The easiest way is to examine the reverse side of the embroidery.

“At the back, you will see a solid tangle of threads, with four or three strands. The lesser the strands, the more difficult it is to embroider, which makes it more exclusive. We do only ‘do-taar’ and ‘ek-taar’ (two-strand and one-strand) Chikankari in our garments. Commercially, you get thicker work with three, four or even five strand threads,” she says.

Lost history

While the craft thrives in Lucknow, its southern Indian variant, which Watt described as “distinct in its preference for silk textiles, with just satin stitch embellishments”, seems to have vanished. Even at the time of the catalogue’s publication, Madras silk embroideries were not classed as Chikan work, but rather as satin-stitch embellishments.

Master craftsman Daday Khan of Mount Road, Madras won the first prize with a silver medal for a series of silk dress pieces embroidered in silk at the Delhi Durbar exhibition in 1903. But it is impossible to find any more links to him or the craft today.

Fashion designers exploring the craft to come up with contemporary designs.

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy: Anjul Bhandari

Paola Manfredi, Italian author of the 2017 book Chikankari, a Lucknawi Tradition, says Watt’s catalogue is essential to understand the lost history of Indian crafts. “The Victoria and Albert Museum in London has a few specimens of Chikan embroidery from Madras that were purchased at that time from the exhibitions and therefore their origin is somehow ‘certified’,” she writes in an email interview.

“Most of the pieces appear to be rather western in style, done in satin stitch. The ‘jaali’ (a net effect created on the base fabric) works are very interesting and different from other forms that were/are popular on Lucknow Chikan. I myself have been planning to extend my research on Chikan beyond Lucknow and I have been looking at other forms and styles although most of them have disappeared today,” she says.

Italian author Paola Manfredi’s 2017 book Chikankari, a Lucknawi Tradition

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

It must be noted that Watt’s catalogue also mentions the ‘Madrasi jaali’ stitch consisting of a series of minute squares, measuring 1/16th inch in diameter. One stitch would be opened, the other left closed, and third would be broken further into four more minute openings. No threads would be drawn out; instead they would be held in position with minute button-hole stitches.

At the Delhi fair, Daday Khan exhibited a variety of women’s dresses with cuffs and panels embroidered in Madras Chikankari. He also displayed tea-table cloths embroidered in ‘washing gold’. “They form a class of goods quite distinct from the extensive series of tea-table cloths from many other towns … those of Madras have a dignity and purity of design all their own that is quite charming,” writes Watt.

It is a pity that the craft has been erased from its south Indian milieu, and even its fate in Lucknow, so to speak, hangs by a thread in the face of automated textile production.

“If you want to keep Chikankari alive, you have to give the artisans their due, or risk losing them to other professions. We have to keep evolving in our marketing. Anyone investing in a Chikankari garment is morally supporting the artisan,” says Anjul.