In a corner of The Aguad, Goa, stands a black velvet female mannequin, on which is draped a metallic bikini-armour — a helmet with bison horns on its head, a curtain of chain mail covering the crotch. Behind it is a large poster showing a model wearing the same costume, with the addition of bat-wings splayed out from her spine.

At the ongoing Prinseps exhibition, Bharat Through the Lens of Bhanu Athaiya, we realise this too is the great artist and costume designer’s creation. But for what project could she have made it? Intrigue dissolves into laughter as curator Brijeshwari Kumar Gohil reveals that Athaiya put the costume together as part of the iconic JVC Onida “devil” ad campaign in 1996.

Iconic is a word that has followed Bhanu Rajopadhye Athaiya for years now. Born in 1920 in Kolhapur into the family of the royal priest, she demonstrated an affinity for the arts and crafts, spurred on by her father who practised carpentry and painting; and after his death, her mother who would send her to Mumbai to pursue her talent. She studied art and art history at the J.J. School of Arts, and was the first woman to be invited to be part of the Bombay Progressive Arts Group — she had a seat at the table along with Modern Indian art’s greatest luminaries like F.N. Souza and S.H. Raza.

For decades, Athaiya has been relegated to little more than a footnote in Indian art history — the answer to “who was the first ever Oscar-winner from India” in general knowledge books. A reckoning with her legacy has been long overdue, if you ask her daughter Radhika Gupta, who has been hard at the task of salvaging and preserving what’s left of her legacy — worn down by time and a white ant infestation — for over four years.

“My mother had trunks full of archival material and wanted to bequeath it to someone,” Gupta says. “Unfortunately, she found nobody who was interested. One person from a ministry did tell us, ‘Aap yahan chhod jao, hum dekhenge kya kar sakte hain [you can leave it here, we’ll see what we can do].’ My mother very firmly told me, ‘I will set fire to it rather than give it away like this.’”

When pop culture met art history

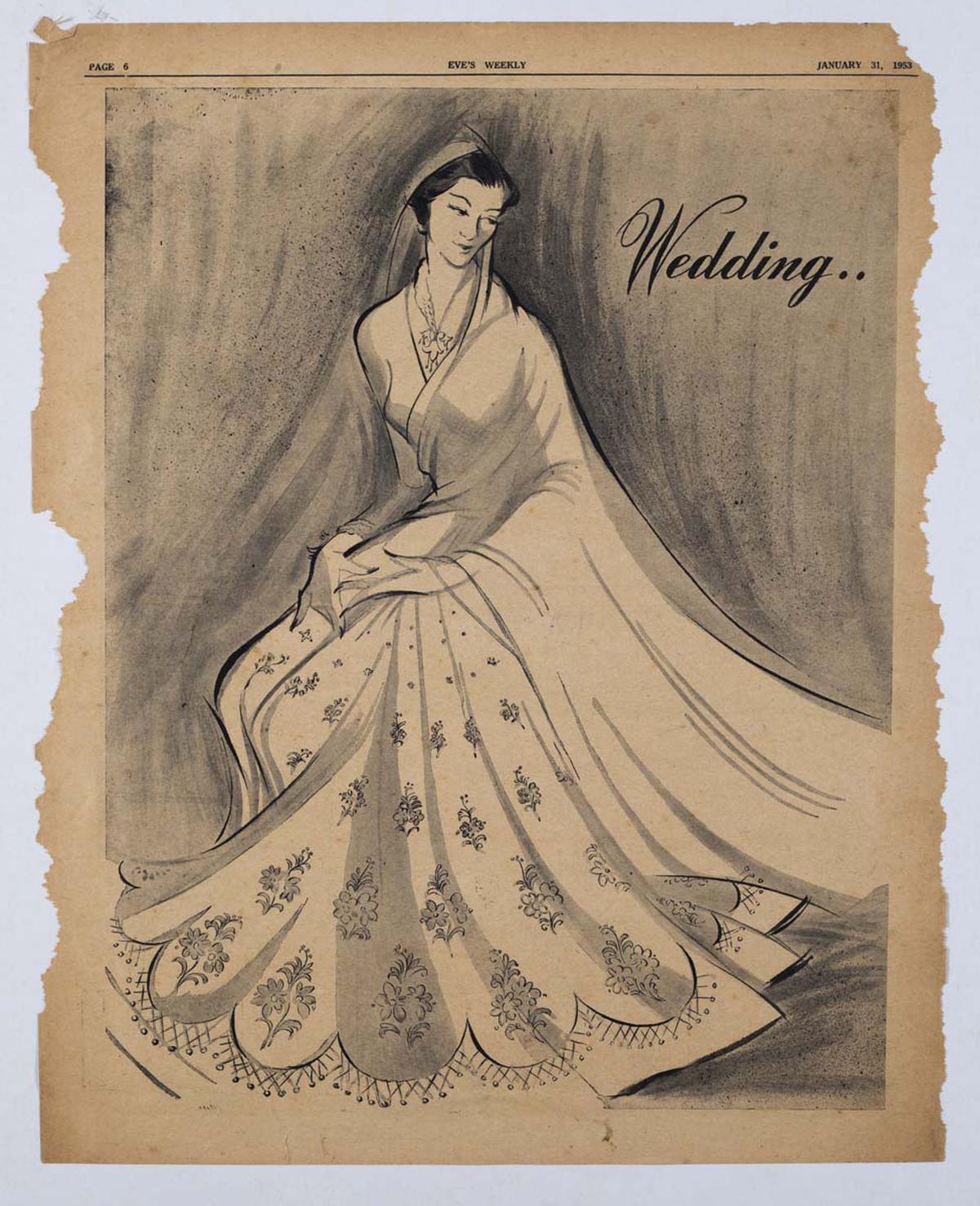

At The Aguad, a museum housed in the Port and Jail complex, you can see the results of this painstaking work, which has been enthusiastically encouraged by Prinseps owner Indrajit Chatterji, and to whom Gupta has signed over Athaiya’s estate. You also walk past display cases with silk saris from her own collection and leaves of a short-lived fashion magazine from Bombay called Eve’s Weekly, with her hand-drawn sketches.

You witness carefully-preserved costumes on mannequins, such as the iconic orange sari for Mumtaz from Brahmachari — the prototype of the now-popular concept sari, and a technological marvel for incorporating the zip for a performer’s comfort.

“When we were studying Bhanu Athaiya’s archives, the family photos, personal paraphernalia, costumes and sketches, the one thing that came through is that India is the land that inspired her,” Gohil says, explaining the theme of the exhibition. “Right now, India is being spoken about so much, in terms of design, craft, textile, art, luxury. And you have this person who made the country cool in all these ways 60 years ago!” Indeed, a survey of her work across a whopping 240 films — beginning with Devendra Goel’s Aas in 1953, right up to Jaypraad Desai’s Marathi language Nagrik in 2015 — reveals her to be that rare figure in popular culture who had an art historian’s eye and a researcher’s rigour.

First of many interventions

If sartorialism was Athaiya’s lens to showcase a post-Independence India, then the body was undoubtedly her canvas. Especially the female form that remained a source of inspiration for her — a trajectory that can be traced back to her days as a young artist, in award-winning paintings such as Lady in Repose.

“Look at some of the western costumes she designed. She was very observant where the actor’s bodies were concerned. Whether it was a drape or silhouette or material, she would use a certain fabric that could accentuate a person’s curviness without making them look puffed up,” says Gohil.

The actor Zeenat Aman, who worked on 16 films in 15 years with Athaiya, was at The Aguad. She confirmed that Athaiya did have a mannequin made in her image, and admitted that the costumes she designed did a fair amount of the work for her characters. She remembered Athaiya as a mild-mannered, gentle but meticulous force who dominated this fledgling industry — indeed elicited greater recognition for it.

Bharat Through the Lens of Bhanu Athaiya is one of many interventions that Prinseps has planned to embellish her legacy in mainstream memory. The team is currently exploring the possibility of donating some of her sketches to the Victoria & Albert Museum, London, while Gohil is looking into Athaiya’s Shakespearean influences, given her work in theatre of which very little is known.

Next up is a large-scale show in Mumbai in 2024, “a sort of homecoming show”. Chatterji is keen to digitally recreate, with AI possibly, the Calico fashion show of 1958, to which Athaiya was invited by theatre director Ebrahim Alkazi. The ideas are many and flying fast. How will they not when, as Chatterji puts it, “Athaiya was fashion before there was fashion.”

The exhibition is on till January 1 at The Aguad.

The writer is an independent journalist based in Mumbai, writing on culture, lifestyle and technology.