Upstairs, in Tarun Tahiliani’s massive Gurugram atelier with exposed brickwork and vaulted skylights, is an 850 sq. ft. room. Twenty-two full-sized glass and wood cupboards, built parallelly, hold 6,000 physical items, including original swatches from his repertoire of embroideries. With crystal, Swarovski, kashida from Kashmir, jamewar, fine-hand aari, zardozi, Parsi gara and resham, the master couturier’s fashion archive also includes textile panels, toiles and tech-packs from his collections.

The archive at Tarun Tahiliani’s Gurugram atelier

Some of the embroideries in the archive

Each numbered item has a designated spot, is hung straight (to avoid creasing that could lead to tears), and is deep cleaned fortnightly. With the temperature consistently maintained at a cool 18 degrees Celsius — and no direct sunlight or harsh lighting to preserve the colour of each textile — it is a space that his team often gravitates to for inspiration and study.

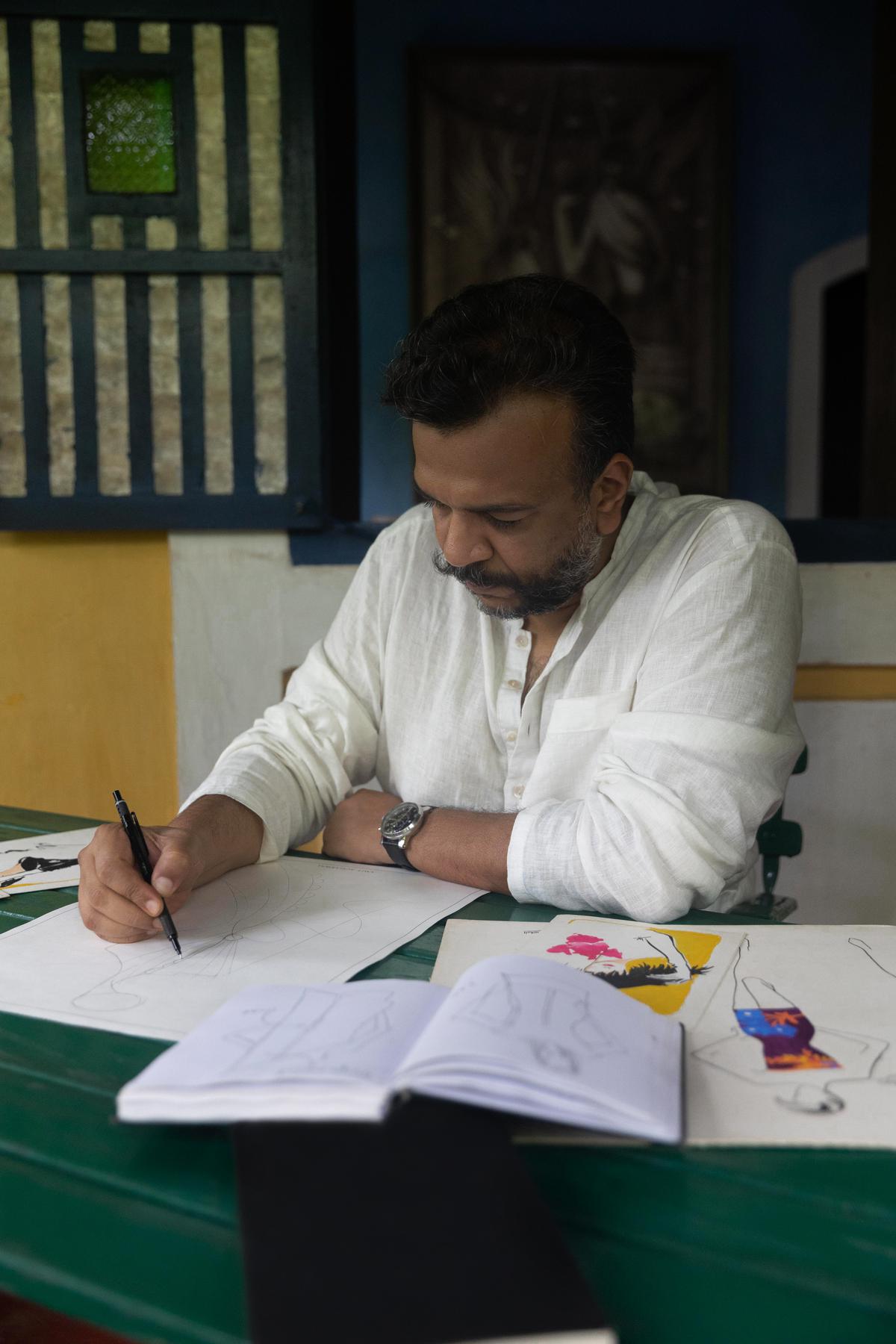

When Tahiliani released his design memoir, Journey to India Modern, last month at Art Mumbai, spanning stories of three decades in the business — from his first show in Milan in 2003 to the beginning of his famous, and now endlessly copied, ‘concept saris’ — no doubt, his archives impacted the book. “The greatest gift working on the book gave me was to remind me of the many things I had done, but forgotten,” says the couturier, adding that in November 2024, he will be exhibiting from his archive at the prestigious Asian Civilisations Museum in Singapore. A first for any Indian.

Tarun Tahiliani

Tahiliani is not singular in his desire to preserve the legacy of his brand. While archiving is still small and nascent among the Indian fashion fraternity, this year has shown many acknowledging it. Last month, veteran designer Payal Jain commemorated her 30 years with textile sculptures of her past work at a retrospective in Delhi. In April, Manish Malhotra’s 90s and early naughts’ movie designs went up on view at the ‘India in Fashion’ show at Nita Mukesh Ambani Cultural Centre (NMACC). And in October, Sabyasachi Mukherjee’s Instagram throwback (a digital archive if you will), to the greatest moments in his career, caused a tizzy on the internet.

Payal Jain’s retrospective

The time keepers

“Milestone years make individuals and companies contemplative. As India turns 76, this trickles down to the field of fashion as well,” explains Deepthi Sasidharan, co-founder of Eka Archiving Services. The one-of-its-kind museum advisory has worked with prominent Indian fashion designers, textile giants such as Anokhi and Fabindia, and jewellery majors, including Amrapali Museum and The City Palace Jaipur, to help bring sense and sensibility to their mammoth collections of clothes and jewellery.

Manish Malhotra’s 90s and early naughts’ movie designs at India in Fashion show at NMACC

How much of a designer archive does a nascent fashion industry like India have, though? After all, India’s first formal fashion week was held in 2000, compared to New York Fashion Week in 1943. That said OG designer Ritu Kumar has a point to make: “What we find of Indian textiles is in the archives outside the country, in museums in London, Vienna, etc — wherever they copied Indian prints.” So, she decided to spend time archiving “what we have achieved in the last 60 years, which has been in a way, a history of India”. Rumour has it, Kumar’s large archive in Delhi consists of over 4,000 rare and historic textile pieces.

Preserving clothes for posterity has not been too important in the fashion industry, which is always looking to the next season. Today, however, designers are realising that their old collections could make for great exhibitions and retrospectives. “I believe past collections make a brand as much as the current. They shouldn’t be forgotten, but celebrated,” says Mukherjee, whose wonderland of a Mumbai flagship store displays pieces from his first-ever couture collection, along with placards recounting stories about his earliest pieces and how he came to develop his signature style. “This is why I built a living archive in our Mumbai store — as a reminder of not just the work and craftsmanship that is definitive of my history as a couturier, but as a reminder of how it remains alive and continues to thrive as part of the current ethos of the brand.”

Sabyasachi Mukherjee

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

Sabyasachi Mukherjee’s Mumbai store

Younger brands such as the whimsical Pero are also keeping in-house archives, helping preserve their origin story. It’s interesting to note how, at Rimzim Dadu’s 15th year celebration last year, at the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art in Delhi, the designer displayed a wall of her failed experiments. No doubt archiving them helped her develop her now signature metal embroidery and sari.

“It is a mistake to consider an archive a graveyard of textiles. What it is, is a repository that needs to be added to continuously”Malvika SinghAuthor and publisher of Seminar Magazine

A designer directory

Maintaining an archive ensures designers are able to have a consistent brand and design language. Barring the late Wendell Rodricks, senior fashion designers in India still run and represent the houses they started, which makes them the primary key holder to the house’s design etymology and values — and often that key is in an unorganised drawer in the designer’s head.

Tarun Tahiliani’s collection inspired by Rai Pannalal Mehta

But with collaborations becoming key (going by the trend of the last few years), it’s essential for the brand DNA to be strong. Which makes room for archiving in the fashion industry. Moreover, the strategic partnership wave created by Reliance Brands Limited (RBL), Aditya Birla Fashion and Retail Limited (ABFRL), and Purple Style Labs, since 2021, has brought transition plans into focus. Many second generation family members now occupy prominent positions within a label, and as the third generation joins the workforce, having recorded history of design becomes the first step to ensure that everyone speaks the same language.

But Sandeep Khosla, one-half of celebrity favourite couture label Abu Jani-Sandeep Khosla, is candid. “Maintaining an archive requires serious financial commitment. When we first started out [in the industry] 38 years ago, resources were limited and the focus was very much on selling,” he says. While their fine chikankari embroidery repertoire deserves a book of its own, over the last few years, the designers have been recreating swatches of their work or borrowing pieces from their clients to build their archives. During the opening of the NMACC earlier this year, Khosla and Jani opened their archives so stylists could source special looks for models and celebrities.

A future blueprint

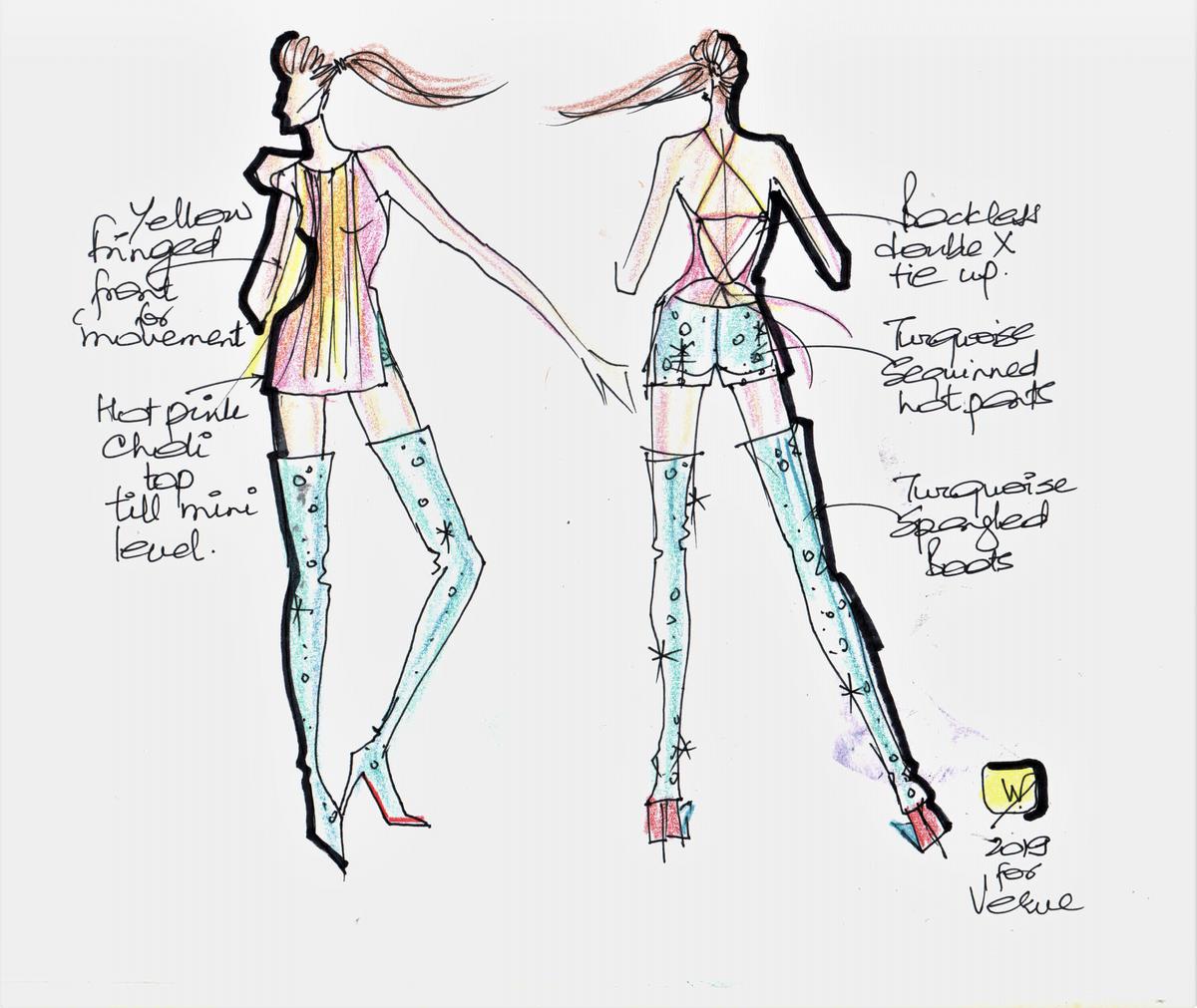

“An important reason to archive is also its final financial value,” says Pramod Kumar K.G., co-founder of Eka. “A sorted archive helps brands increase their acquiring cost with conglomerates.” Abhishek Agarwal, founder of Purple Style Labs (PSL), whose company acquired Wendell Rodricks’ brand in 2020, furthers the thought: “The archives of the late designer played an instrumental role in the acquisition. Everything created now is done keeping in mind the core ethos of the label. Be it the sketches Wendell drew sitting in his quaint Goa home, his intervention with Kunbi saris, his old interviews, photoshoots, or fabric samples, PSL meticulously preserved every piece and they continue to inspire the label’s designs to date.” The recent Amit Aggarwal x Wendell Rodricks collaboration dipped into the archives. Aggarwal, who is known for his sculptural cuts, studied Rodricks’ draping and size agnostic silhouettes to create a fresh susegaad-meet-sexy collection.

Amit Aggarwal sketching at Wendell Rodricks’ Goa home

Fashion sketches from Rodricks’ archive

Malaika Arora in a Amit Aggarwal x Wendell Rodricks design

Documenting and digitising

When archiving, it’s not just about arranging collections in chronological order. It requires detailed segregation and filing of inspiration boards, yarns, resource libraries, textiles, embroidery swatches, contacts of karigars, personal anecdotes, sketches and family heirlooms that impacted the design process. It takes many months of ardent book-keeping to arrive at something substantial.

Tahiliani hired Delhi-based Gurvinder Kaur, a research scholar and PhD in Indian traditional and contemporary textiles and fashion, to maintain his archive. Kaur and his team meticulously worked on documenting and digitising each piece from his archives, adding detailed information about the design techniques involved. Eka also worked with him on restructuring his archives.

Building archives is useful for in-house teams and students. Like in the case of designers David Abraham and Rakesh Thakore. The label enlists young textile design students from NID and NIFT, for whom the opportunity to go through Abraham & Thakore’s early and ongoing experiments with ingenious textiles is a priceless experience.

Abraham & Thakore’s archive

Abraham & Thakore’s early and ongoing experiments

Some of their interventions with ikat, in a houndstooth or leopard spots pattern, are incomparable and form a key part of their archives. “Divia Patel, senior curator of the South Asian Department at V&A museum, was really the reason we started archiving formally,” shares Abraham. “She saw that we used to throw away our sketches, and old pieces were unorganised in boxes. Being a museum curator, she really stressed the importance of being methodical, as we start thinking of our future plans for the brand.”

Three to start

Kishore Singh, DAG’s head of Exhibitions & Publications, shares his tips:

1. Archive beyond just the obvious — i.e., your collection. This should include surrounding material such as films, shows, plays, books released around the time that could have influenced a collection, notes on world events, etc. The point you arrive at once you finish collecting all this is the nucleus.

2. Prioritise information on the people who worked on the collection — the actual artisans and craftspeople. The pattern cutters, weavers, embroiderers all need to be credited correctly and in-depth.

3. Source material: detailed information on where the materials for the collection were acquired, who made the weaves and its technical counts should be mentioned in the books.

The writer is a Mumbai-based fashion stylist.