A pillar here, an elaborately carved door there, trellised balconies and stone carvings offer tantalising glimpses of what it must have been like 2,000 years ago when Paithan, then known as Pratishthana, was the capital of the mighty Satavahana dynasty, and later the Vakatakas, the Yadavas and the Marathas. The town located a little more than 50 km from Aurangabad city was a bustling hub of trade, money and great influence.

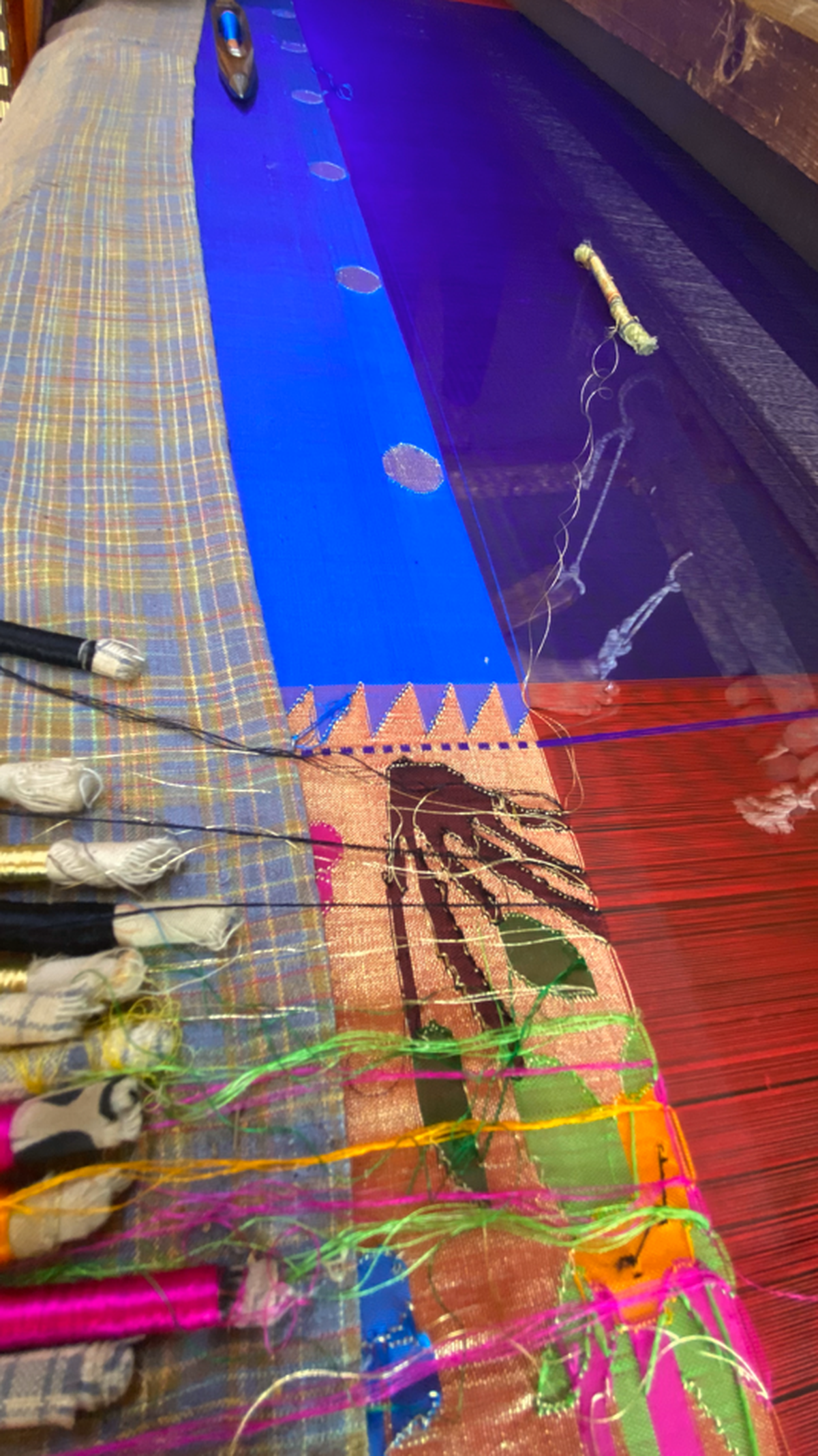

A Paithani weaver at work

| Photo Credit:

Vishal Magar

Some of that buzz was briefly recreated recently when locals and textile aficionados from the country converged to visit Kāth Padar — Paithani & Beyond, an exclusive exhibition organised at the Shri Balasaheb Patil Government Museum. Presented by Maharashtra’s Directorate of Archaeology and Museums along with Pune-based The Vishwas & Anuradha Memorial (TVAM) Foundation, it was an attempt to shine a light on the rich and ancient heritage of the place where the Paithani sari found expression.

Kāth Padar — Paithani & Beyond exhibition in Paithan

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy of TVAM Foundation

Mayank Mansingh Kaul, an independent researcher, writer and curator, who worked closely with TVAM’s founder-chairperson Rasika Mhalgi Wakalkar for over a year to give shape to the show, believes that today culture has become far removed from the people, it has been ‘museumified’.

Mayank Mansingh Kaul and Rasika Mhalgi Wakalkar at Kāth Padar

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy of TVAM Foundation

“There is a need to take such educational formats of textiles to artisan centres where there is an active community of textile makers. The exhibitions [of handspun, handwoven textiles] that I’ve had the chance to curate at Chirala, Coimbatore, Hampi, Jaipur and Paithan have all emerged from this need,” says Kaul, who has an abiding interest in post-Independence histories of textiles in India. “My belief is that such exhibitions need to go beyond formal institutions and address audiences beyond the big metro cities.” A belief that is justified: he recalls 4,000 weavers visiting the Chirala exhibition (in 2018) in the space of a week, and coming back to visit over and over again.

“These initiatives are vital as they reach audiences that are often overlooked, and include them in these very essential conversations on culture. As Mayank demonstrated in Hampi [at Red Lilies, Water Birds, an exhibition of handwoven textiles conducted last November], where the exhibits were beautifully mounted in small village homes, it takes a clear statement of intent that is coupled with a certain design ingenuity to make these exercises possible in many different environments across the country.”David Abraham Creative director of fashion brand Abraham & Thakore

Such initiatives are especially vital because the sad truth is that in a country with an incredibly rich history and variety of handwoven textiles, documentation is lax. While few are stepping up to fill the gaps — in Bengaluru, The Registry of Sarees, a research and study centre founded by Ahalya Mathan, is attempting an interdisciplinary approach that enables design, curatorial and publishing of projects in the area of handspun and handwoven textiles, and Varanasi has recently started a centre dedicated to showcasing its weaving techniques — there’s room for much more.

Initiatives such as this help. “At a time when there is a surplus of confusing mis-representation in Indian textiles, exhibitions such as Kāth Padar bring clarity of hands-on learning from the source of a cultural textile practice. They create bridges where once only pockets of isolated learning existed,” says Mathan. “These are more inclusive, experiential ways to understand the culture behind textiles that would otherwise be seen only through geographical contexts. Links based on weaving technicalities and practices may now be furthered between weaving communities across the country.”

What can textile exhibitions do?

According to Kaul, exhibitions such as these “create a physical platform for a non-commercial educational format. They can be the ‘curriculum’ in the absence of training modules in textiles”. He believes that exhibitions backed by research will narrate textile tales in an accessible manner so that the information is inspirational pedagogy. “They can be taken out of big cities into a different demographic, and they also highlight the importance of archiving and creating an archive.”

“Through initiatives such as Kāth Padar, we experience a culture through the window of the past. It is a way to decolonise the past and introduce us to skill sets that we struggle to replicate now. Exhibitions such as these are a product of interdisciplinary studies where textile designers, archaeologists, historians, artists, writers, and conservationists all contribute so much.”Ahalya MathanFounder, The Registry of Sarees

A deep dive into Paithani

Paithani, with its jewel tones in fine silks and embellished with floral and bird motifs, is a textile of the Deccan. They were expressions of the power and prestige of the dynasties that ruled over this region, especially the Maratha aristocracy. The delicate and expensive Paithani was sought after as far away as Rome and anecdotal references say that Roman brides wore them!

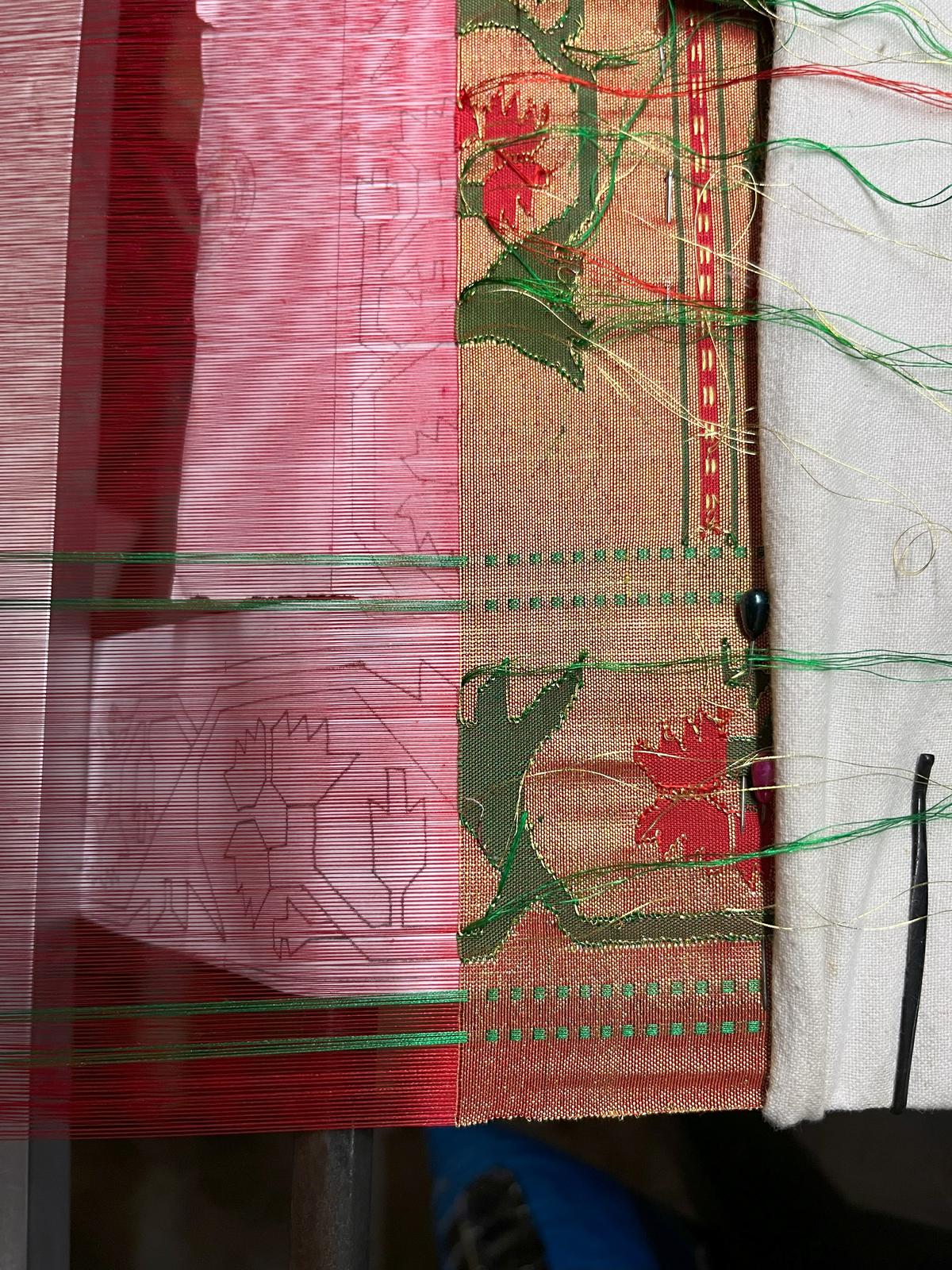

The intricate borders of the Paithani

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy of TVAM Foundation

A shela (left) and a Paithani sari

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy of TVAM Foundation

The 20 pieces on exhibit include saris, voluminous shelas (shawls) usually worn by men, safas or turban cloth, and borders. “The Paithani is not a singular identity; it has connections to different weaving traditions, and has travelled far and wide. Some of these textiles incorporate something of jaamdaani, the Irkal, and Chanderi,” says Kaul. “The motifs on some of them have a visual similarity to Kashmiri shawls. Other motifs, such as the lotuses, are reminiscent of the art in the Ajanta caves. There is also evidence that the Nizams of Hyderabad were keen patrons and instituted workshops to revive the Paithani.”

A Paithani headgear

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy of TVAM Foundation

The historical pieces have been drawn from the collections of the Shri Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Museum in Satara, the Shri Bhavani Museum and Library, Aundh, the Nagpur Central Museum in Nagpur, and private owners.

Bollywood connect

Designer Nachiket Barve loves the Paithani and has worked with it extensively. He commissioned special Paithanis for the 2020 film Tanhaji, about Shivaji Maharaj’s trusted lieutenant. “I am now working on a Marathi Film, Maan Apmaan, which again uses a lot of Paithani saris as it is set in an aristocratic milieu and is about a fictional princess,” he says. While Barve believes that seeing traditional textiles on screen has the potential to revive interest in them, the celebrated Maharashtrian textile will thrive only when it enters the ‘coveted list’ across demographics, the way the Benarsi has.

“Rasika and I went through a map of Maharashtra and identified at least 50 Maratha families. We met several of them in Miraj, Gaganbawda and Baroa, as well as parts of Madhya Pradesh,” he says. “We began with our assumption that Paithani was a trophy textile that got patronage from the wealthiest aristocratic and royal families. And, of course, we visited the state museums, from where many of the exhibits are drawn.”

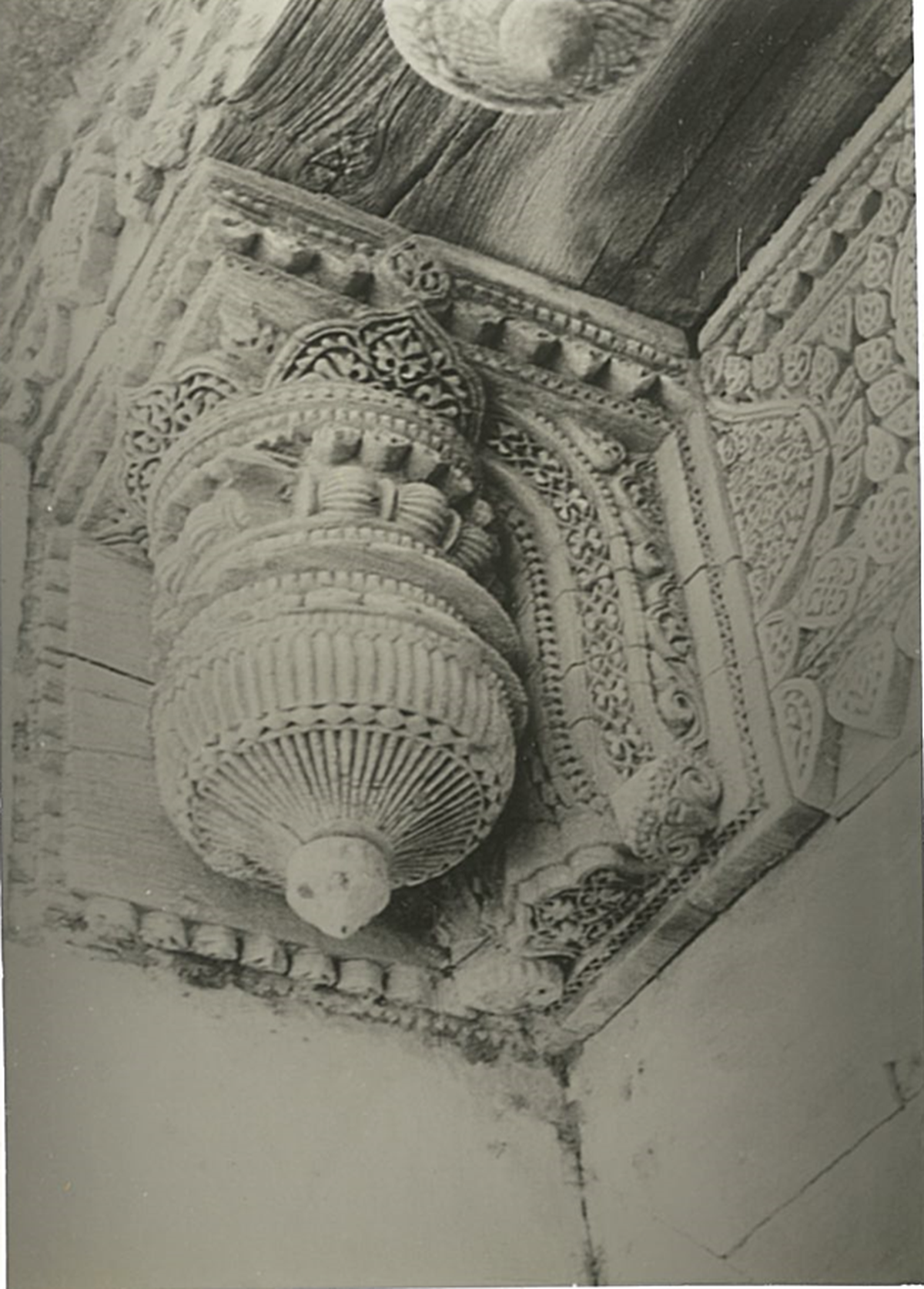

A lot of the planning and research undertaken by TVAM for the exhibition were based on the seminal work of historian R.S. Morwanchikar, from his thesis titled Paithan Through the Ages, and his book Paithani: A Romance in Brocade. “Dr. Morwanchikar has been the foremost scholar on Paithan for the last 50 years,” says Wakalkar. “The black and white photographs of woodwork in Paithan that you see at the exhibition were taken by him in the 1980s. He has donated over 200 photos and positives to TVAM, for our research purposes.”

Black and white archival images of Paithan’s wood carvings were part of the exhibition because the designs have been replicated in the textiles

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy of TVAM Foundation

Carved facades of old Peshwa houses in Paithan

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy of TVAM Foundation

The woodwork in Peshwa houses

| Photo Credit:

Vishal Magar

Resources in the local language were invaluable too, adds Kaul. “Sushma Deshpande’s PhD in Marathi on the costumes and dresses of the Peshwas [the second highest office in the Maratha Confederacy] gave us meticulously recorded details. She is now writing about references to the Paithani in Marathi literature and poetry.” A lot of historical resources, unfortunately, are from the western world, he says, and were viewed through a prism of the colonisers. While they are a valuable source, much is often lost in translation and lacks local nuances. So, the conversations Kaul and Wakalkar had while putting together the show, and the resources available in the local language went a long way in ‘decolonising’ the information.

An experience to be replicated

Even if such exhibitions at artisan centres cannot be identical or templated versions of each other, due to the difference in environment, space, communities and infrastructure, they can be driven by the same sentiment and spirit, believes Kaul. “In Hampi [at ‘Red Lilies, Water Birds’, an exhibition of handwoven textiles held last November], we did not have a museum like we do in Paithan, so the exhibits were mounted in village houses. In Coimbatore, known for some of the world’s finest mill-made cotton, the ‘Meanings, Metaphors’ exhibition [housed in a mill] made a statement about the handmade.”

Government support is important for this. The Ministry of Culture Affairs aided Kāth Padar by fast-tracking meetings, ensuring funding and quick approvals. “There was support right from the level of the minister to the local staff at the museum,” says Tejas Madan Garge, the director of the Directorate of Archaeology and Museums, adding that he believed collaborations with experts will revitalise traditional textiles. “The state government museums are a rich repository of source materials, and such exhibitions could be replicated in other state departments as well.”

Creating archives

One of the outcomes of Kāth Padar will be to ensure proper documentation of motifs, weaving techniques and colours of Deccan textiles, especially for the weavers. “A weaver weaves to sell. Forty or fifty years after a sari leaves a weaving centre, the weaver or his children will have no sample directory or archive to refer to,” says Wakalkar. “What that means is that markets will dictate design decisions depending on what’s ‘selling’ more. The look and feel of a Paithani has changed today. I won’t say if that’s good or bad, but it was one of the reasons to undertake this project. It’s an open invitation to weavers, scholars, designers, traders, patrons and buyers, to participate in the conversation, and have their own take-aways.”

“Through initiatives such as Kāth Padar, we experience a culture through the window of the past. It is a way to decolonise the past and introduce us to skill sets that we struggle to replicate now. Exhibitions such as these are a product of interdisciplinary studies where textile designers, archaeologists, historians, artists, writers, and conservationists all contribute so much.”Ahalya MathanFounder, The Registry of Sarees

Building a bridge

Meanwhile, weavers from Paithan are coming forward with information and samples of old pieces that they or their parents and grandparents have woven — which is significant when even the Paithan museum doesn’t have an old Paithan textile. “This is the kind of response that is so gratifying,” says Wakalkar, as she admires a copy of an old Paithani sari richly woven with peacocks, parrots, lotuses and creepers. It was made by a family member of Shameen Bhai, a master weaver himself.

A Paithani weaver

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy of TVAM Foundation

Shantilal Bhandge, an 80-year-old weaver of the Paithani sari, who visited the exhibition on its first day, shares that he was overjoyed to see the historical textiles. “Rarely does anyone weave saris like that any more; it would be too expensive. But, if weavers today see this collection, they will be inspired to raise the bar [there are around 300 weavers in Paithan and neighbouring Yeola]. There is so much beauty in the details,” he says. For instance, the exhibited borders depict lotuses that look like they were painted on, underlining the use of the interlock tapestry weaving technique to bring out colour tones. “Kāth Padar gave me a lot to think about,” adds Bhandge, who won the National Award in 1991.

“Exhibitions such as these presented outside of the big cities allow for a new audience who are local and often more aware of the traditional aspects of the woven textiles on display than their urban counterparts. ”Lekha PoddarCo-founder, Devi Art Foundation

Having more researchers collaborate with state governments to host textile exhibitions in small towns will also encourage conversations that will raise awareness and access to information. “A lot of times, heritage collections are not open or accessible. A book or a catalogue is informative, but seeing examples of the work is a very different thing,” says Sucharita Beniwal, co-lead of textile design at Ahmedabad’s National Institute of Design, who encourages her students to visit as many exhibitions as they can. “More so in environments removed from big metros, you see the textiles in another light and context. It is an important format that has to come up.”

The writer is a freelance journalist based in Coimbatore.