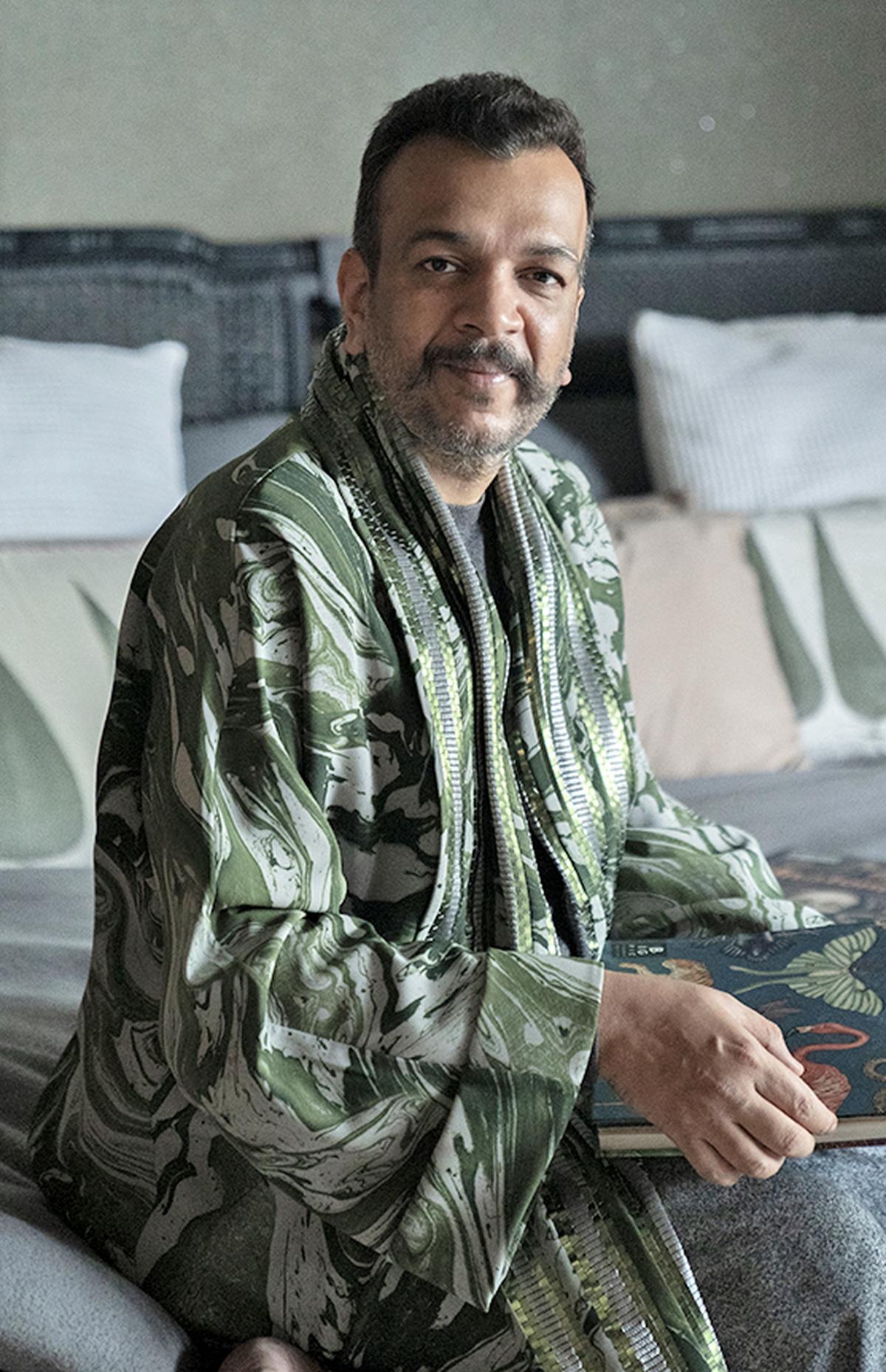

It takes a village, and then some, to craft Tilla’s Kabira and Rosa jackets. The one-of-a-kind pieces feature thread and metallic embroidery, reversible designs, and multiple colourways. The patchworked base is a highlight, stitched by women from Pindharada village near Gandhinagar, using leftover fabrics and off-cuts from the Ahmedabad-based label’s archives.

“As a clothing design studio, we generate a lot of cutting waste,” says Aratrik Dev Varman, designer and founder of Tilla. “I have, over the years, very consciously collected every bit of scrap hoping that we could make something of it.” A conversation with Jaai Kakani, who runs the NGO Soach, on upskilling rural women, led to a project where Dev Varman and his team created a training module for sewing. The collaboration has culminated in the label’s ‘Recycle’ collection, comprising jackets and dresses. Dev Varman continues to work in Pindharada, and plans to extend to quilts and textile art.

Tilla’s Kabira and Rosa jackets

| Photo Credit:

Rohan Doshi

Aratrik Dev Varman

| Photo Credit:

Rohan Doshi

As conscious craft and zero waste goals take over design thinking, fashion labels are becoming more mindful of waste. A decade ago, the number of garments produced in the world exceeded 100 billion, and a 2017 Global Fashion Agenda report estimated an annual figure of 92 million tonnes of textile waste globally. These numbers are still cited, though the volume of both production and waste has likely increased since then. India is among the world’s top regions for sourcing apparel and textiles, and according to a 2022 report by Fashion for Good, it accounts for 8.5% of global textile waste — with approximately 7,793 kilo-tonnes generated every year.

Designers and upcycled patchwork

The process of making garments yields plenty of leftovers, from fabrics to trimmings. A number of homegrown labels — both big and small — are repurposing this production waste using methods that range from traditional techniques to material experiments. Take for instance, the House of Anita Dongre, which generates 2,000 kg of textile waste every month (as per estimates on its website). The company, known for its mindful designs and sustainability initiatives, works with organisations such as Goonj, an NGO that undertakes disaster relief and humanitarian aid, and NEPRA (National Electric Power Regulatory Authority), and its own tailoring unit to create godharis (quilts), bags and other items.

Designers such as Amit Aggarwal, Urvashi Kaur and Bodice by Ruchika Sachdeva have collaborated with Paiwand Studio to make capsule collections from their production excesses. At the Noida-headquartered studio, upcycling waste is a multi-layered operation. Textile scraps sourced from the industry and craft clusters are handwoven into new fabrics and made into garments.

Amit Aggarwal

Last week, Aggarwal launched his ANTEVORTA collection at the Hyundai India Couture Week, which, as per his signature, used industrial materials and recycled polymer sheets. “We worked with pre-loved Benarasi saris [for ANTEVORTA]; our signature cording techniques reinforced the fabric and breathed new life into these age-old textiles,” says he designer. “We also employ techniques like fusing, melting, and stitching to merge contrasting materials, such as polythene with chanderi.”

Couturier Varun Bahl has developed a patchwork signature from his archival pieces, incorporated in lehengas, sherwanis, jackets, and saris. “We use the same embroideries and archival [embellishments] to create upcycled fashion, as well as older threads and buttons,” says Bahl, who first showcased such designs during the lockdown. “This year it has become 30% of our collection and very soon it will be 50%.”

Bahl’s upcycled patchwork designs

Varun Bahl

Quilts for the win

Production leftovers are inevitable, even in conscious studios. “There is little wastage in the way we design garments,” says Chinar Farooqui, founder of the clothing label Injiri. “What is left over is yardage, which usually comes in 11-metre lengths from handloom weavers. After a garment is constructed, the last 10 to 20 inches tend to remain.”

At Injiri’s Jaipur headquarters, the team upcycles leftovers for up to a year following a collection. “Quilts and mattresses are the best application because they consume a lot of textiles — a quilt requires 9-10 metres of textiles, and mattresses can take up 5-6 metres,” she says. “We also add value to the designs, with cutworks and appliqué.” The label’s recycled quilts stand out for their eclectic mashups — one quilt is colour-blocked with fabrics in over a dozen shades, while appliquéd botanical shapes in dark colours offset an ivory base on another.

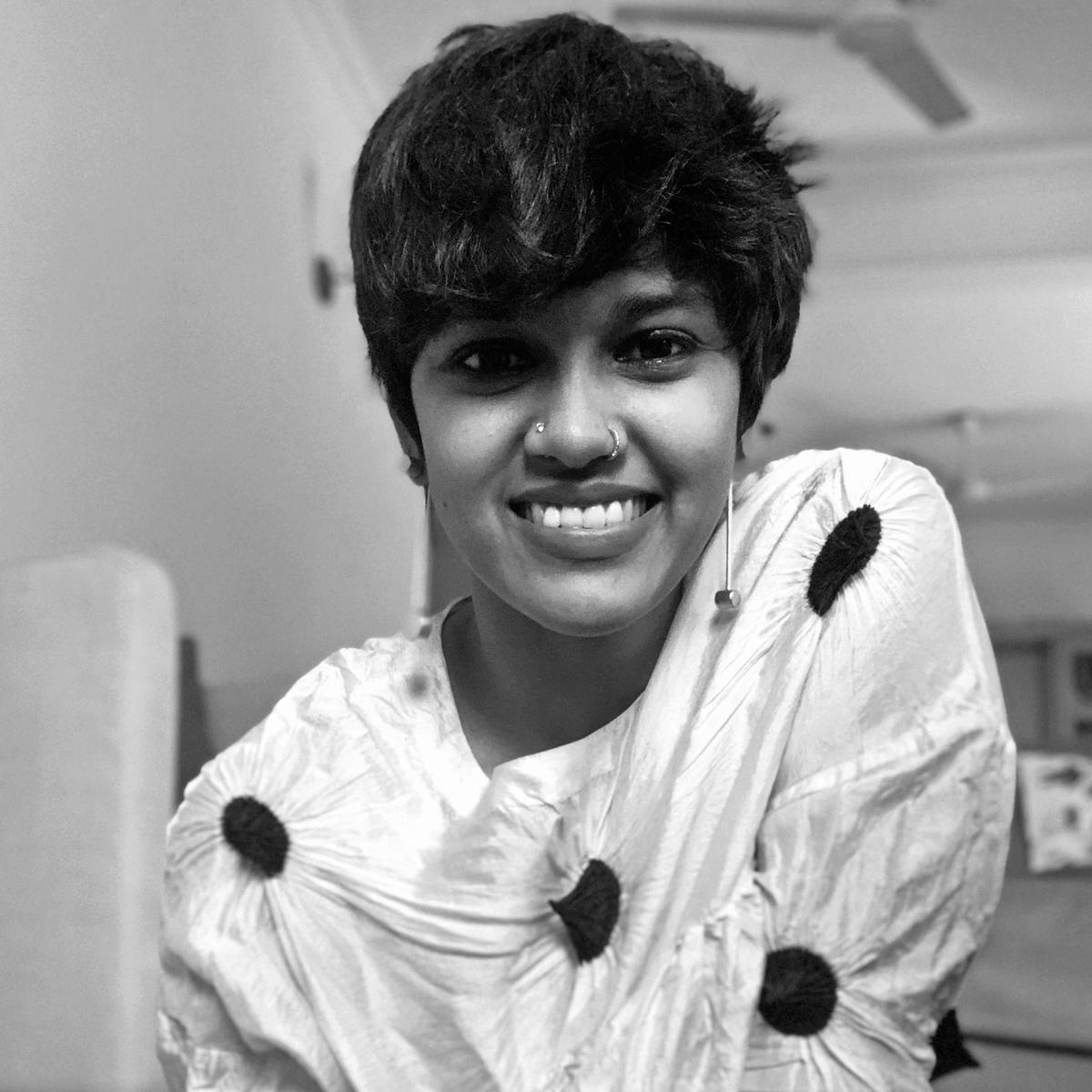

Chinar Farooqui of Injiri

| Photo Credit:

Julie Hall

Injiri quilts

Injiri’s choice to make quilts and mattresses is rooted in tradition. Communities across India, from Gujarat to Bengal, recycle old clothes and stray patches into household items. And the singularity of such textiles is both a selling point and a challenge. “We have to consider logistics such as space and organisation of fabrics,” says Farooqui. “Since no two pieces are alike, it takes energy and time to conceive of products that work.” Injiri patches new yardages from these leftovers too, and has recently created a line of jackets.

Designer-led labels such as Ekà and péro use production waste in imaginative ways, from clothes to packaging. “We do a lot of activities around leftover fabrics. There are three diffusion lines that utilise scrap. Eka Core uses old archival textiles and re-purposes it, like overprinting and dyeing,” says Rina Singh of Eka. Fabrics are also incorporated in their home and children’s line, in packaging and the label’s block printing processes.

Working with leftovers

Designers also integrate leftovers into new apparel. For Harshna Kandhari and Mannat Sethi, co-founders of Delhi-based emerging label Graine, the key lies in introducing subtle details and modular elements such as detachable layers. “There’s a satisfaction we feel, being able to pick waste from the brand and reimagine them,” says Sethi. One of Graine’s signatures is the River jacket, which the label introduced two years ago, stitching together organza leftovers to create textured patterns. Most recently, in their Spring/Summer 2024 collection’s Sublime Jacket Dress, “we also made pockets with waste fabrics to which we have added chikankari”, says Sethi, who is now reusing metal parts and waste embellishments.

An outfit from Graine

Jebin Johny, founder of the label Jebsispar, draws attention to another kind of production waste: defective printed fabrics. “I once received a batch of saris that couldn’t be used because of printing issues,” he recalls. These included the label’s signature St. Thomas prints from their ‘Nasrani’ collection and motifs from the ‘Kathakabuki’ line, among others. Johny has gradually incorporated elements from those saris as statement motifs using appliqué techniques on dresses and separates as part of the ‘Kintsugi’ collection, which are now among Jebsispar’s bestsellers. “I am also working on a new collection using all our scraps and leftovers,” he says.

Jebsispar’s upcycled dress

Jebin Johny

Reusing bandhani thread

At the Delhi-headquartered label Studio Medium, material innovations from waste are offered under their Future Tense initiative. Its most distinctive offering is a material created from the threads used to make bandhani and tie-dye fabrics, and usually discarded after. “The [thread waste] attains a form and texture due to the way it is used,” says founder Riddhi Jain, who first developed these textiles as a student at National Institute of Fashion Technology (NIFT) over a decade ago. “It carries a memory of the process it has been through, and that has always been exciting to us.”

Jain has applied the material to create apparel, furniture, upholstery, small goods, and textile art. According to the brand, each textile or garment from discards uses an average of 1.5 kg pre-consumer waste; the team has used over 300 kg yarns and off-cuts so far. “It has taken time and experimentation to figure out scalability and means of reusing on a regular basis,” she says. This included making new blueprints and training artisans to undertake the operations. “We are now working very hard on a collection that’s entirely monochromatic.” A Future Tense website is also in the works.

Riddhi Jain

Bandhani threads

A Future Tense jacket

Labour intensive

Setting up upcycling infrastructure requires time and resources. Paiwand Studio aims to serve this need, consulting designers, brands, and export houses on waste management and creating upcycled textiles and capsule collections using their waste. Founder and creative director Ashita Singhal notes that developing new textiles can be an expensive process for brands; in her studio, the process involves cleaning and sorting waste based on colour and raw materials, creating strips and bobbins which are then handwoven or embroidered to create new raw materials for garments.

Ashita Singhal

Additional man-hours and intensive production raises manufacturing cost to as much as producing a regular collection; this in turn affects retail pricing. “But if everyone uses and upcycles their scraps, it will drastically change material consumption patterns,” she says. “It can save costs, generate employment, and impact the environment positively. Small efforts bring big changes.”

The writer and editor is based in Delhi.