In recent years, the conversation has only deepened with the proliferation of streaming platforms, giving more space to some works deemed ‘controversial’. Some argue that filmmakers are ‘rewriting history’, while others believe there should be ‘no limits to creative freedom’. It’s an ongoing debate that questions the boundaries between art and responsibility.

How Much Creative Freedom is Too Much?

The views of directors, actors, and industry insiders vary greatly when it comes to the extent of creative freedom filmmakers should have in historical films. While some advocate for “complete creative liberty,” others stress the importance of maintaining a sense of “responsibility” toward historical facts.

Filmmaker Sudhir Mishra argues that creativity should flow freely, without restrictions. “As long as it’s not leading to violence, or instigating hate, anything should be allowed through your cinema,” he says, sharing his belief that filmmakers should have the freedom to tell their stories as they see fit. “We are getting too sensitive,” Mishra remarks and warns that stifling creativity will lead to a larger intellectual stagnation. “Whether it is ‘Kerala Story’ or ‘The Kashmir Files’ or my film ‘Afwah’, everything should be allowed. I think, we are getting too sensitive. If you stop the creativity of young people, then they’ll stop thinking,” he opines.

Meanwhile, writer and director Siddharth P Malhotra, takes a more nuanced approach, acknowledging the necessity for some creative freedom while cautioning against distorting facts. “Creative freedom to enhance the movie theatre experience without distorting facts—that much should be allowed,” Malhotra insists. He maintains that filmmakers have a responsibility to respect the essence of historical material and entertain the audience without tampering with the “soul” of the story.

On the other hand, Joachim Rønning, director of films like ‘Maleficent: Mistress of Evil’, emphasizes the importance of being truthful to the story. He highlights that although some aspects of a character’s life might require editing for the sake of a narrative arc, the goal should be to stick as close to reality as possible. He says, “I think it’s very important to be truthful.”

In contrast, Suman Kumar shares this view, stressing the absolute nature of freedom in art. “There should not be any conditions applied to it. Freedom is absolute.” He believes filmmakers should be allowed to “tell the truth” and that restrictions can dilute the integrity of storytelling.

Balancing Fact and Fiction

The delicate balance between storytelling and historical accuracy is also an ongoing concern in show business. Filmmaker Apurva Asrani acknowledges the difficulty of staying true to both, saying, “There are things you can create and then facts that you need to stick to.” Asrani, like Malhotra, believes that while filmmakers can imagine aspects of a character’s personal life, they must stick to the larger, more public facts of historical events.

For actors like Iwan Rheon, the distinction between then and now complicates the representation of history. He says the key is striking a balance between accuracy and present-day sensibilities. Reflecting on his TV show ‘Those About to Die’, set in Rome 79AD, he says, “I think what’s important when you’re watching something that is based on history is on today’s standards, what we would morally consider to be horrific things, in those times, they certainly weren’t. Yeah, there was horrific stuff going on, but it’s a different time. And we try to learn from history.”

This tension between historical fidelity and creative expression is echoed by actor Rhys Ifans, who played the infamous historical figure Rasputin in ‘The King’s Man’. For him, embodying a historical character is an act of interpretation and subversion. “We are allowed in cases like this, to embellish and shape the character,” he says, noting that the fun comes from the space given to actors to reimagine their roles within certain confines of truth. “I found Rasputin very liberating to play. Visually, with a big wig and beard, it acts as a bit of a mask and frees you up. To indulge my own innate sense of mischief and subversion, that’s as far as it goes,” he said.

An Increasingly Intolerant Audience

As public outrage over certain films has escalated in recent years, many in the film industry believe this reflects the broader climate of intolerance toward artistic expression. Sudhir Mishra asserts, “I don’t think we should submit to these things. This is wrong. The state has to look after people who make cinema. It is an expensive medium.” He feels that despite a mechanism in place to review films, external forces have been exerting too much influence over how films are received. He adds, “I don’t think there should be anyone outside the extra-constitutional people reacting. Because then anyone can react to anything, there is no limit to it.”

In contrast, Suman Kumar holds a more optimistic view. He believes, storytelling requires honesty. If you are honest about it I don’t think you will face trouble.” For Kumar, artistic interpretation is inherently subjective, and the audience’s interpretation often strays far from the creator’s intent. “Any work of art is open for interpretation,” he says, suggesting that controversy often arises from a fundamental disconnect between the filmmaker’s vision and public perception. “I do read that this particular show or film got in trouble, but I personally don’t think there should be any intervention.”

The Role of Disclaimers in Protecting Artistic Freedom

Disclaimers have become a crucial tool in navigating the fine line between artistic freedom and public sentiment, especially in historical films and series that have landed in controversy. They are often seen as protective shields, allowing filmmakers to explore sensitive topics while distancing their work from direct claims of factual accuracy. As seen with projects like ‘IC 814: The Kandahar Hijack’ and ‘The Kerala Story’, disclaimers serve to preempt backlash by clarifying the elements of fiction or the interpretative nature of the content. However, their effectiveness in safeguarding against public unrest or legal challenges is limited. While they may offer legal protection, filmmakers like Siddharth P Malhotra and Apurva Asrani agree that disclaimers do little to prevent criticism or controversy. The public, driven by emotion or political sensitivities, may still find offence, regardless of these cautionary notes.

Malhotra, who is more sceptical about the power of disclaimers to shield filmmakers, believes they serve a legal function but ultimately cannot protect creators from criticism. “Disclaimers can’t shield filmmakers from controversy,” he says flatly and adds, “It does the job of telling people that the film is not meant to offend anybody.”

Suman echoes this view, considering disclaimers a mere technicality. He says, “They can shield you, legally. You can claim that ‘we already showed this disclaimer’. If people get offended by something it doesn’t matter whether you have put a disclaimer or not, they will get offended.”

Sudhir Mishra, on the other hand, questions the efficacy of disclaimers, arguing that they often cater to those who deliberately cause trouble, “Why shouldn’t disclaimers work? I think because we are encouraging people who make trouble.” Looking back at the uproar created during the release of his film ‘Tamas’, he says, “People don’t create problems, it’s some vested interests that do. I’ve been a personal victim of all this, we were pulled out of the theatre and the industry stood by and watched.”

Interestingly, Apurva adds another layer to this debate, suggesting that while disclaimers might work in some cases, “If you are marketing the film by gaining mileage from the ‘real events’, then you need to be ready to face the questions too.” For him, the balance between factual accuracy and artistic interpretation lies in being clever about how stories are framed, especially in politically sensitive times.

The Politicisation of Cinema

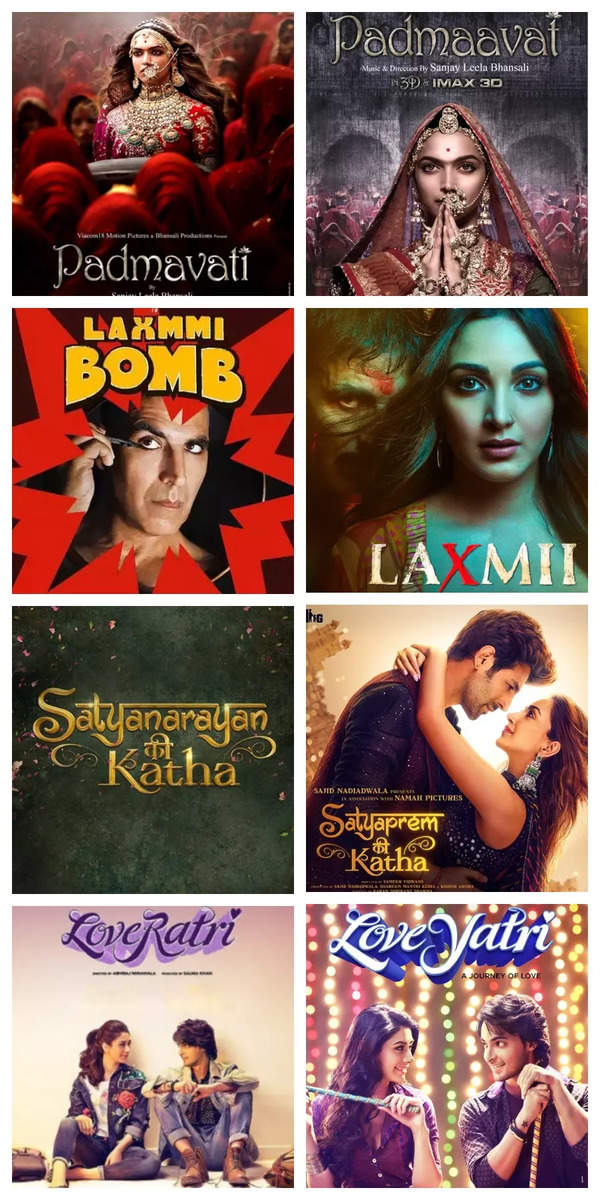

Political and fringe groups in India have repeatedly targeted Bollywood filmmakers over alleged ‘inaccurate portrayals’ of history, religion, or social issues. These groups often resort to legal action, protests, or even threats of violence to stop film releases. One of the most infamous examples is the Karni Sena’s violent opposition to ‘Padmaavat’ (2018). The group claimed that the film distorted the image of Rajput queen Padmavati, leading to physical attacks on the film’s director, Sanjay Leela Bhansali, and vandalism of film sets. Actress Deepika Padukone, who starred as the queen, faced death threats, including a bounty placed on her head.

Similarly, just last year, political groups stirred up controversy over the song ‘Besharam Rang’ in Shah Rukh Khan’s film ‘Pathaan’. On claims of hurting sentiments, some political groups ordered a ban on the film claiming offence over Deepika Padukone’s saffron bikini in the song.

Other films like ‘Jodhaa Akbar’ (2008), ‘Ae Dil Hai Mushkil’ (2016) were caught in political crossfire. Director Karan Johar had to even apologise for casting Pakistani actor Fawad Khan during a period of heightened India-Pakistan tensions.

Other instances include filmmakers being ordered to change the title of their films and character names just before the release to avoid legal action and backlash.

The politicisation of cinema has become an unavoidable reality in today’s landscape, where historical narratives and sensitive themes are often subject to political scrutiny. This in turn has a significant impact on the creative process, especially on historical films. Malhotra candidly states that filmmakers are often restricted in what they can portray, even in biopics. Citing an example of his film ‘Maharaj’, based on Indian Journalist Karsan Das, he says, “There’s a lot about Karsan that I could not say, there’s a lot about the story that should not be told or should be told.”

He went on to add, “I don’t think I have done complete service to Karsan Das’ life in the way it should have been. He was a far greater human being and there were too many prejudgments and preconceived notions for things to come out the way they have. I’m glad people have still appreciated the film and it’s universally declared a hit.”

Elaborating further on the challenges of telling stories on true events, he says, “There are too many emotions involved and everybody’s sentiment will have to be kept in mind when you’re telling a historical or a biopic because it’s connected to someone or some emotion or some sentiment.”

This sentiment is shared by Asrani, who notes that different governments impose different restrictions on storytelling. “There is no way anyone could have made a film critical of the ‘Emergency’ 10-15 years ago, but today there is the freedom to do that,” he says, illustrating how political climates directly influence the stories filmmakers can tell.

The debate over creative liberty in show business is far from settled. While some argue for complete artistic freedom, others insist on the need for restraint when dealing with historical narratives. As films continue to push the boundaries of storytelling, the line between creative expression and historical distortion remains a contentious one.

Anubhav Sinha and Journalist Engage in Heated Exchange Over ‘IC 814’ Controversy