Summary

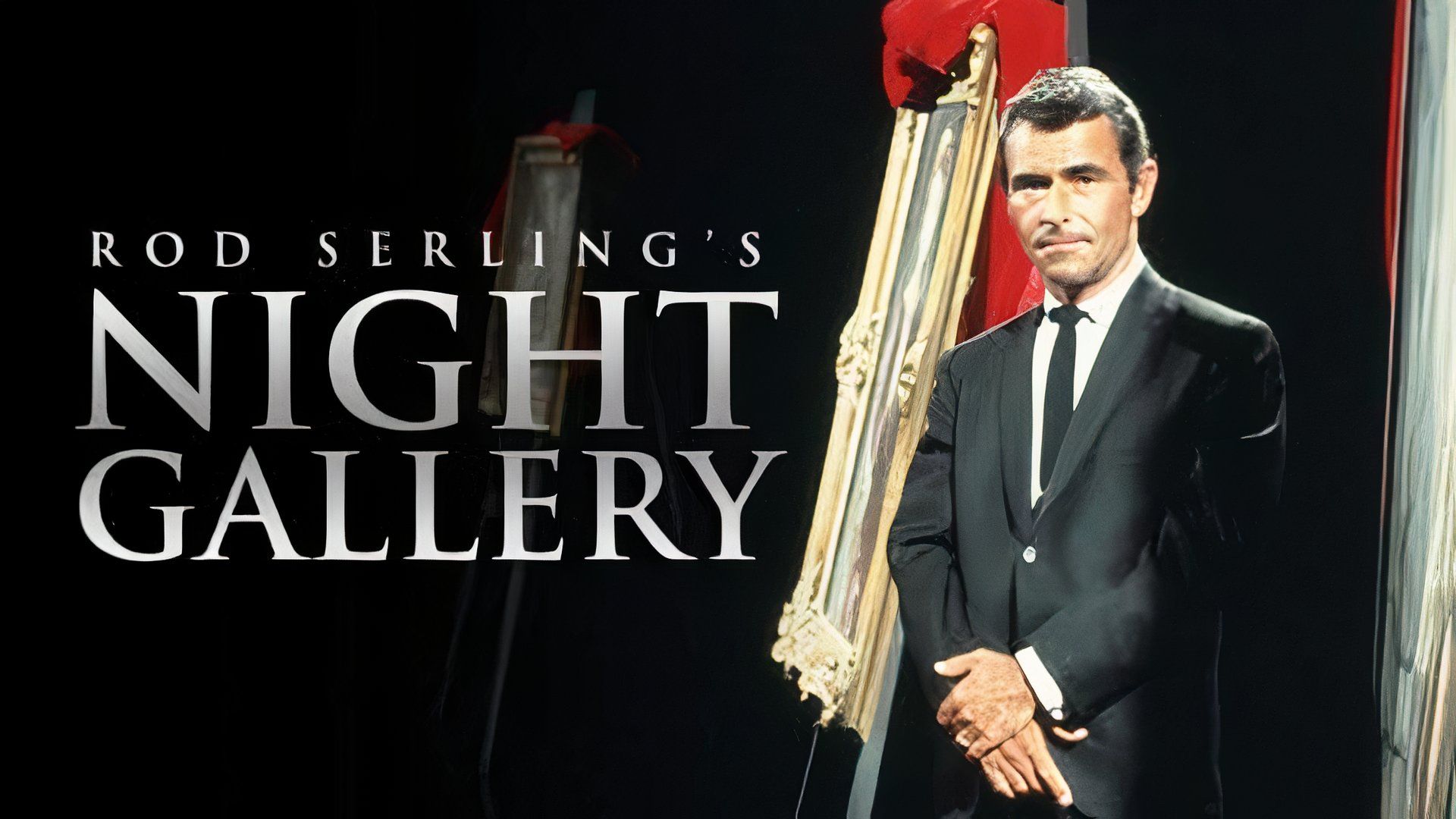

- Rod Serling’s

Night Gallery

, the television follow-up to his legendary

Twilight Zone

series, was plagued by petty disputes and domineering producers. -

Night Gallery

had notable guest stars and pedigree but fell short of its potential due to the limitations of network TV, which favored predictable formats and styles. - Steven Spielberg’s experience directing

Night Gallery

highlighted the suffocating constraints of TV in the seventies, in stark contrast to the adventurous film scene reinventing Hollywood.

In the TV horror and sci-fi genres, few names carried as much weight as writer Rod Serling. While he didn’t create the concept of the anthology — an unconnected series of stories with a new cast and plot each week — he did perfect it. His place in the medium of television is so solid that even those who don’t know his name or face probably still know his voice and his ideas. Serling was the mastermind behind the legendary Twilight Zone, which aired between 1959 and 1964 on the American broadcaster CBS.

Eager to return to the TV medium after The Twilight Zone wrapped up its run on CBS, the author pitched what was essentially a clone to NBC, only this time titled Rod Serling’s Wax Museum. With a few minor tweaks, swapping the setting to a macabre salon, NBC eventually picked up the show and aired the pilot in 1969. Casting the show with a rotating stock of new talent was never the show’s dilemma. Graying legends, established stars, and untapped up-and-comers flocked to the program.

The show lucked out and found ample directing prospects as well. One of those raw, young creative types was Steven Spielberg. Like Serling, Spielberg would come to witness the ugly inner workings of network TV, one in which they betrayed their material, opting to craft the most accessible, generic slop possible to never risk offending any segment of the population, and especially any sponsors. Night Gallery never did live up to its potential, and Serling was the first and most vocal critic. Here’s why.

Cult Classics Don’t Pay the Bills

The ex-Twilight Zone host wasn’t afraid to fess up that TV was a joke in terms of how it treated science fiction. The grounded, less futuristic ideas worked better. The budgets were limited, and thus the scope and focus of any sci-fi program had to be equally downsized, which is why so many Twilight Zone episodes were filmed on cramped sets with rarely more than four actors in a whole episode. In a foreshadowing diatribe in 1970, the author lamented that money is always a concern in making sci-fi. A ballooning budget would be one of the contributing factors to the cancelation of his new show three years later:

“Television, however ambitious it may be, and however vast is the realm of imagination you can dabble in, is still a strangely limited and enclosed and closeted kind of medium. […] We’re the poor relation of science fiction in the mass media.”

No one held it against him, and The Twilight Zone gained more followers after it went off the air, broadcast continuously in syndication, where most shows simply disappeared. A number of those kids grew up to be inspired to become writers and directors in their own right. One of those fans was a kid named Spielberg, who came to epitomize the compromised waste of talent that was Night Gallery.

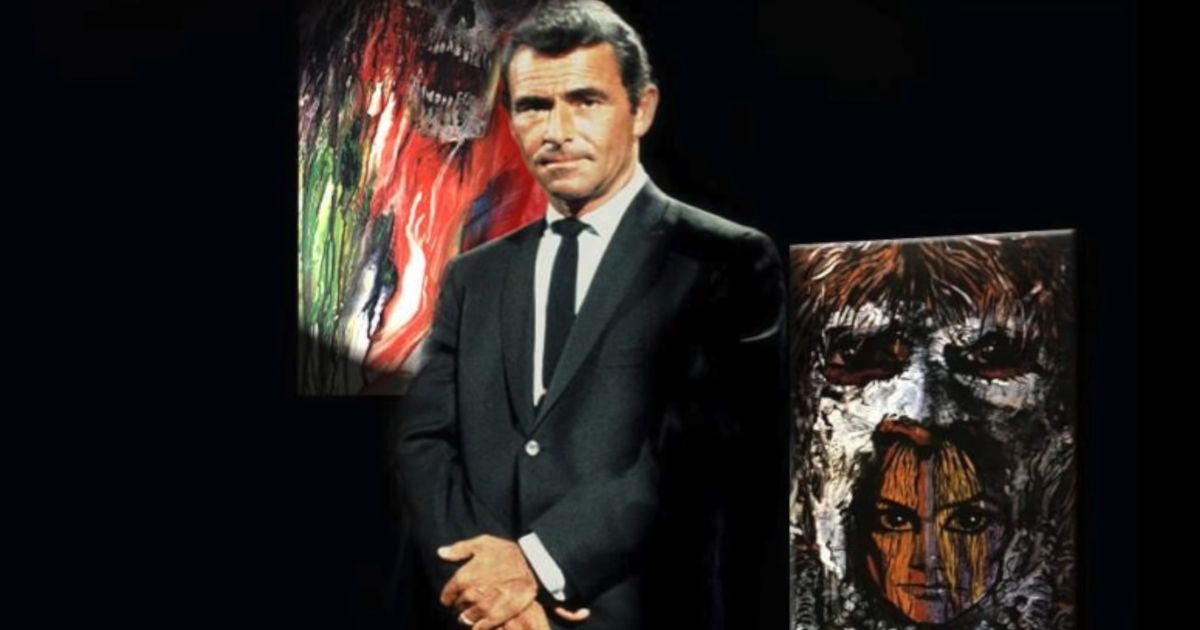

Fans knew exactly what to expect when Night Gallery was announced. Same Serling, same boring suit, same cigarette, same demeanor, same wit, just with longer sideburns. To differentiate the show from his earlier sci-fi/fantasy anthology, this one would hinge on the literal framing device of a macabre art museum, the paintings illustrating themes or scenes from that segment. The vast majority of these paintings were executed by Tom Wright, acquiring their own cult status among fans.

Riding the fame of Serling’s reputation as a thoughtful, fearless author and screenwriter, the show immediately garnered the sci-fi and fantasy communities’ attention. Stephen King singled out the “Caterpillar” as his favorite story in the show’s run (based on a short story written by Oscar Cook). Though the episode titled “They’re Tearing Down Tim Riley’s Bar,” conceived and penned by Serling, is typically deemed the high point of the anthology’s 98 individual segments. Of the program’s bumpy three-year lifespan, the episode sustains one of the best scores on IMDb.

How Night Gallery Was Sabotaged

True to its legacy as Twilight Zone 2.0, many former stars from Serling’s prior venture made the move over to the new show, including Burgess Meredith, Leonard Nimoy, and Dean Stockwell. Guest stars Leslie Nielsen, Edward G. Robinson, Sally Field, Yaphet Kotto, and Mickey Rooney were complemented by unknowns Mark Hamill and Diane Keaton. So far, so good.

Television was long considered a “writer’s medium,” but Serling knew better. “I see scripts of my own on television, and I wonder who wrote them!” he once complained to interviewer Dick Cavett shortly before his death in 1975. Though the show was pitched and greenlit on the back of his writing credits and sheer power of personality, his boss saw him as a third wheel. On national TV, Serling all but disowned the show, telling Cavett in a scathing sit-down that the TV show that bore his name meant nothing to him.

By the time of this interview, it’s impossible not to notice the Night Gallery host’s disillusion and bitterness, airing all the dirty laundry of his life in the TV trenches. He’d effectively checked out of the show and industry by 1972, fed up with others dumbing down his plots, watering down its messages, censoring the merest hint of politics, and turning it into just another forgettable show. Steven Spielberg was fortunate. Sadly, Rod Serling’s long battle against TV execs, producers, and sponsors was a losing battle he would never win.

Night Gallery was a final humiliation in an otherwise illustrious and influential career in TV and movies. Producer Jack Laird and story consultant Gerald Sanford rewrote Serlings’ scripts, adding in new content that didn’t fit the theme of the original pilot, discouraging him from even attempting to write anything whatsoever, claiming his stories were too long. The show ran roughly the same length as The Twilight Zone, but it never came close to the level of quality. If you want to see the truest form of his vision, look to his more obscure films or books, not his TV projects.

Related

Best Rod Serling Scripts Outside The Twilight Zone, Ranked

Explore the legacy of Rod Serling’s writing through his most famous works outside of The Twilight Zone and the lasting impact of his great writing.

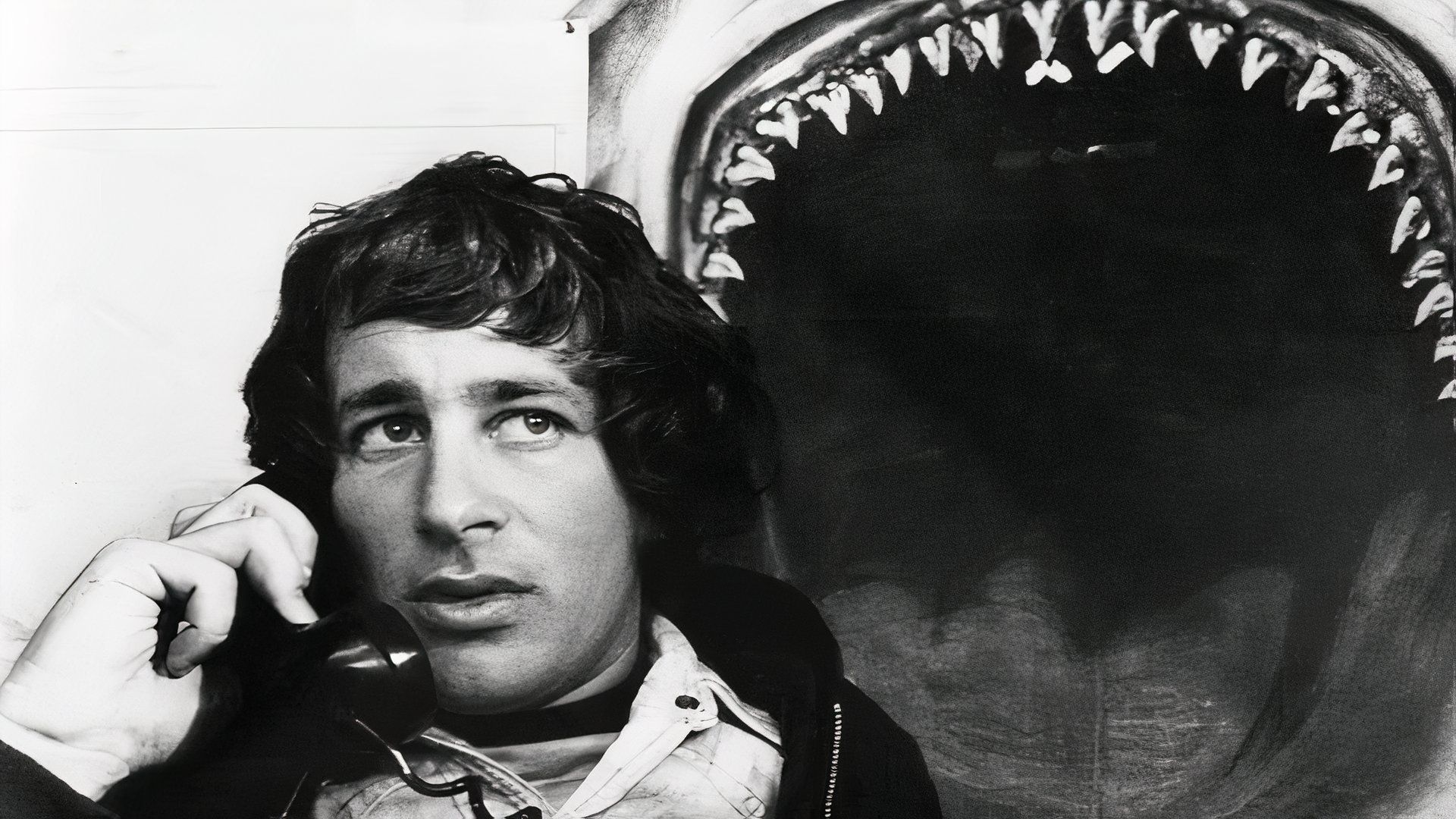

Steven Spielberg’s Short-Lived Television Career

Serling’s issues with the showrunner (back then just called a producer), extended well beyond the script-writing, and he was hardly the last one to feel the impact of the show’s spreading artistic rot. Steven Spielberg, then barely 20, got his big break directing the pilot episode starring Joan Crawford. Completely out of his element, he held his own, and reportedly had a very friendly experience working with the notoriously difficult actress, despite his barren filmography and lack of insight into how a professional production operated. In 1969, Spielberg still hadn’t finished film school. Truth is, he was better off making indie movies where he had a modicum of freedom.

Volatile actresses were one thing. Producers are quite another. Spielberg was another casualty. Called back for another go around, he opted for a highly innovative (regardless of how gimmicky it seems today) single shot that would comprise his allotted section of the hour-long episode in season one. The only limitation was the limited space on a reel of film, amounting to ten minutes max. Spielberg needed to fill 11 minutes for his part of the show titled “Make Me Laugh.” He claimed to have devised a workaround to the problem, but we’ll never see it. That segment was canned and lost forever, as he told Stephen Colbert in 2023.

Related

Steven Spielberg Reveals the ‘Best’ Film of His Storied Career

Steven Spielberg is “proudest of” this movie he made.

Through a clever use of multiple sets, he pulled off a seamless edit that appeared as if it was a single shot, unheard of on television because of its complexity. “They were appalled,” Spielberg said of the NBC network execs when they laid eyes on the preliminary footage. He surrendered many of the expected visual flourishes, blocking, and camera angles that television dramas had established over the last two decades. There was an absence of close-ups and framing devices as a result of the way Spielberg chose to approach the segment. For his trouble, he was permanently banned from ever directing another episode.

He got the last laugh, directing a segment for Twilight Zone: The Movie, which he also produced. That nameless exec later apologized. Spielberg recovered, young enough to shake off the humiliation and quickly move on to bigger and better things. Serling was not so lucky, dying two years after the show was canceled. We can only wonder what it would have looked like if he had complete control. Night Gallery is currently unavailable to stream but you can purchase the show on DVD.