In the last week of December, Perry Cross Road in Mumbai’s Bandra suburb, which has hosted streetwear favourites such as Jaywalking, Mainstreet Marketplace and Bhavya Ramesh, will also become home to New Delhi-based circular fashion label Rkive City’s next experiment: a 400 sq.ft. repair shop.

It is a wild step for a young brand, but not for Ritwik Khanna. All of 26, energetic, carrying the sort of undaunted, reckless optimism that powers start-ups and late night sewing rooms, Khanna says, “It may not make sense financially to repair other people’s clothes, but it’s not a marketing activity either.” He is calling it an impact play. A kind of designer-led CSR where instead of discarding their beloved or not-so-beloved clothes, people can reimagine what they were ready to bin. “We want to gamify the concept of repairing, where you can get your frayed pieces patched or fixed, with a cool contemporary play on it.”

Ritwik Khanna

| Photo Credit:

Abyinaav

Love me again

Repairing or rafugari is not new in Indian parlance. Patchwork, quilting, kantha, darning, even Japanese boro that conscious labels such as Studio Medium and Padmaja propagate follow the same zero-waste instinct, where torn or roughed up pieces earn second lives with more character than the first.

But what does a designer repair shop charge? Khanna laughs at the question and then answers it seriously: “We are not going to be functionally the biggest repair store in the country. That is still someone like the tailor uncle who sits close to Galleries Lafayette [in Kala Ghoda] and is capable of repairing anything. But it will reflect a designer intervention.” And with that, a higher price point. Not for mending, but for recontextualising.

Khanna is aware that in India repair has always been tied to lack. “Someone who worked at OLX explained to me that the way Indians need to be marketed second lives is not with the shame of buying pre-owned but by encouraging selling.” This small insight sits alongside the mountains of post-consumer textiles he has accumulated. Together, they form the beginnings of a new system. “Circular Design Challenge at Lakme Fashion Week [India’s biggest award for circular fashion, which he won last year] gave me a platform, but I do believe we will see de-institutionalisation of brands moving away from fashion week formats,” he says.

For a young designer to show confidence outside the system reveals where their minds are now. It mirrors a generational shift, too. While Millennial designers once chased international runways and couture conquests, the younger lot really does want to save the world, but not by stopping people from buying clothes. Instead they want to build parallel worlds, ones that make clothes last longer, and loop back.

Khanna, who comes from a family of clothing exporters, faced resistance when he refused to join the business. “I told them I would work in the clothing market but in my own way.” He now works with his 21-year-old brother Aarav, collecting discarded clothing bits and seeing them in a completely different light. “As impossible as it may seem I’ve put certain codes in place for how we want to arrange the discarded bits, colours, materials.” Rkive, the brand they co-own, often posts images of their mountainous collections of degenerated clothing, pieces they later pull apart and rebuild through cuts, patterns, repairs.

Old uniforms and red socks at Mayo

Khanna carried this same restless energy into the night of his first solo show recently at his old stomping grounds in Mayo College Ajmer. His cast included former teachers, young models, current students and hotelier Abhimanyu Alsisar.

The audience was an equally eclectic roll call. Young Jaipur prince and princess Pacho and Gauravi Kumari (Khanna’s friends and batchmates), alumni and friends such as artist Paresh Maity, designers Amrit and Gursy of Lovebirds, Ruchika Sachdeva of Bodice, photographers Bharat Sikka (whose studio is next to Khanna’s in Delhi), Prarthna Singh and Rid Burman, jewellers Samarth Kasliwal of Gem Palace, and Digvijay Shekawat of Sunita Shekhawat all watched from the sidelines.

Bharat Sikka, Amrita Khanna and Gursi Singh at the show

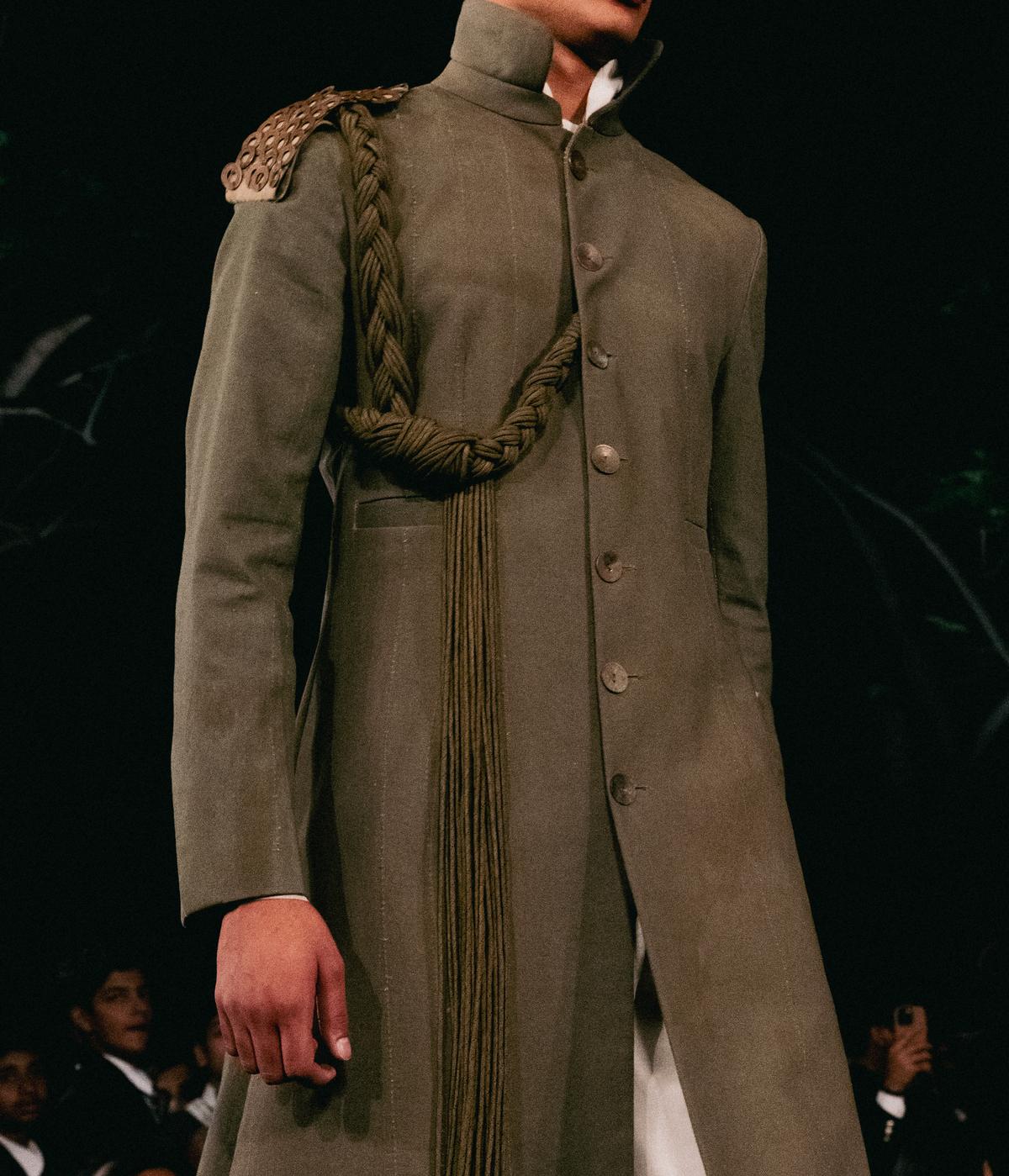

The show marked a milestone at his alma mater. Mayo College, in its 150th year, had celebrated with polo matches, concerts and a gathering of old and new students. Khanna’s show slipped neatly into the mood, then twisted it. He pulled from the college’s history and Rajasthan’s visual codes, tugging the familiar slightly off-centre. Uniforms were taken apart and rebuilt into cropped breeches, collarless bandhgalas, trench coats, deconstructed denims, corduroy jackets, pockets printed upside down and the crowd favourites, panchranga pieces five coloured, bold striped seperates, made from the school’s five coloured tent cloth.

A school tie and antique coin, reimagined as a brooch

Discarded linens, old uniforms, and decades-old curtains resurfaced as medals, coins, rings, safas and ties recast into buttons and badges. Made entirely from what the campus had quietly stored for years, it gave a new meaning to kids singing “we don’t need no thought control.” And ever the rebel, Khanna insisted on red socks on the models. A colour that, according to school lore, annoyed teachers and wardens, but boys wore anyway to attract the attention of girls.

A white blazer and pachranga shorts, styled with red socks

Back in Mumbai, I have one last question: “how do you mend a relationship?” Quietly he replies, “Space first, then be the first to apologise.” Khanna’s optimism proves torn clothes can have a new lease at life, and with a little patience, perhaps relationships, too.

The writer is a Mumbai-based fashion stylist.

Published – December 20, 2025 10:51 am IST