In the heart of the Sahel, a geopolitical earthquake is unfolding — one with global implications. Mali, once hailed as a fragile but hopeful democracy emerging from colonial shadows, is now at the edge of outright jihadist rule. Al-Qaida’s regional affiliate, Jamaat Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM), has steadily tightened its grip across the country’s vast northern and central regions. What began as an insurgency in the sands of Timbuktu and Gao has evolved into a political, ideological, and territorial movement poised to reshape the balance of power across West Africa. While headlines often fixate on global flashpoints such as Gaza, Ukraine, or the South China Sea, the Sahel is quietly becoming one of the most consequential battlegrounds in the struggle between state collapse and militant ascendancy.If Mali falls completely — and indications suggest it might — it would mark the first time since the fall of Afghanistan in 2021 that an al-Qaida-linked force effectively seizes and governs an entire country.

The anatomy of collapse

Mali’s downward spiral did not happen overnight. In 2012, Tuareg separatists launched a rebellion in the north, declaring the independent state of Azawad. Their advance triggered a military coup in Bamako and fractured the already fragile Malian army. Into this chaos stepped Islamist fighters — many trained and battle-hardened from Libya’s post-Gaddafi wars — who quickly hijacked the Tuareg uprising. By late 2012, the black banners of jihad were flying over northern Mali’s ancient desert cities. French troops intervened under Operation Serval in 2013, pushing the insurgents back. For a brief moment, it seemed Mali might stabilise. Yet a decade later, the insurgency not only survives — it dominates.

The departure of French forces in 2022, following deepening resentment from Mali’s military junta and an influx of Russian Wagner contractors, accelerated the deterioration. Wagner prioritised regime preservation over territorial defense, leaving rural communities to fend for themselves. As a result, JNIM moved rapidly, establishing its own shadow administration — collecting taxes, enforcing Islamic justice, and mediating disputes in areas where the state had withdrawn completely.JNIM has effectively partitioned the country, not by storming the presidential palace with technicals, but by executing a sophisticated “anaconda strategy” — strangling the state economically, isolating its military, and negotiating the surrender of its rural periphery.Today, more than 70 percent of Malian territory is either under jihadist control or contested. The government’s presence is largely symbolic beyond Bamako and a handful of garrison towns surrounded by hostile territory.In July 2025, JNIM began a strategy to blockade the government-controlled cities from foreign fuel imports and to cut them off from each other. Mali depends on foreign fuel imports, receiving 95% of its fuel from Senegal or Ivory Coast.From September, JNIM imposed a blockade against cities in southern Mali, including the capital Bamako, after the government had stopped fuel sales in rural areas.In October 28, the US Embassy advised all American citizens to leave the country immediately because of increasing instability, and to do so by plane, because of “terrorist attacks along national highways”.In November, 5 Indian nationals were kidnapped by armed men suspected to be affiliated to JNIM.

The rise of JNIM — al-Qaida’s African vanguard

Founded in 2017 as a coalition of several jihadist factions operating in Mali and the broader Sahel, Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin has crafted a uniquely localised model of insurgency. It blends al-Qaeda’s transnational ideology with pragmatic alliances tailored to West Africa’s ethnic and social dynamics.

Led by the veteran Tuareg militant Iyad Ag Ghaly, JNIM has perfected a patient strategy of “winning by embedding.” Instead of seeking rapid conquest, it integrates itself into local communities, co-opting grievances against corrupt officials, abusive armies, and tribal rivalries. Its fighters often act as mediators in disputes, offering security in exchange for loyalty. Over time, it has built a proto-state structure that rivals the government’s reach — especially in Mopti, Ségou, and Gao regions.Unlike the Islamic State’s West Africa Province (ISWAP), which favors spectacle and brutality, JNIM focuses on sustainability. It courts local legitimacy, leverages social hierarchies, and imposes justice systems that, while harsh, often function more efficiently than the absent state bureaucracy. This approach has earned it cautious acceptance — even quiet collaboration — from some rural populations desperate for order.

Erosion of the Malian State

The Malian government’s predicament is profound. Since staging two coups between 2020 and 2021, the military junta led by Colonel Assimi Goïta has struggled to project authority beyond the capital. Economic sanctions, diplomatic isolation, and overdependence on Russian military contractors have hollowed out state functions.

In key northern towns like Kidal and Menaka, state symbols have disappeared. Schools operate under jihadist permission, Islamic councils collect taxes, and local markets pay levies to JNIM. The national army, poorly trained despite years of international aid, rarely ventures far from fortified bases. When it does, columns are frequently ambushed by militants armed with anti-tank mines and improvised explosives. Satellite imagery and NGO mapping confirm what locals already know: stretches of the Sahel once marked by sparse governance have now turned into jihadist heartlands. Civilians who interact with the government risk retaliation from militants. The result is a self-reinforcing vacuum in which fear, faith, and fatigue sustain the insurgency’s dominance.

Wagner gamble

Mali’s invitation to Russia’s Wagner Group was meant to stabilise the regime and counter Western influence. Instead, it deepened the crisis. Wagner’s operations, centered on protecting key infrastructure, mines, and the presidential palace, rarely extended to protecting civilians in remote areas. Reports from the central Mopti region, verified by human rights monitors, indicate that Wagner’s counterinsurgency tactics rely on mass detentions and collective punishment — approaches that alienate local populations and feed jihadist recruitment. In several notorious incidents, including the 2022 massacre in Moura, eyewitnesses described Russian fighters and Malian soldiers executing unarmed villagers on suspicions of aiding militants. Such brutality, while intended to intimidate, has had the opposite effect.Meanwhile, Russia benefits economically from access to gold and uranium concessions. For Bamako’s rulers, Wagner offers regime survival. For ordinary Malians, it means living between two predatory forces — one foreign, one ideological — both indifferent to the human cost.

The abandonment of the West

Western disengagement from Mali reveals a broader fatigue with so-called “forever wars.” After France’s withdrawal, the European Union’s training mission followed suit. The United Nations peacekeeping force, MINUSMA, was ordered by Mali’s junta to depart by the end of 2023. Its exit marked the largest UN drawdown in years — and one of the most abrupt.The consequences were immediate. Within weeks of the UN withdrawal, JNIM seized several former peacekeeping bases and expanded its influence westward toward Kayes and Koulikoro — regions once considered secure. Intelligence offered by departing foreign forces was not transferred to local authorities, leaving an intelligence blackout. Humanitarian actors now describe vast “no-go” zones where aid delivery is impossible.The irony is striking: while Western capitals proclaimed “African solutions for African problems,” they left behind a battlefield primed for jihadist domination and regional contagion.

Domino Effect

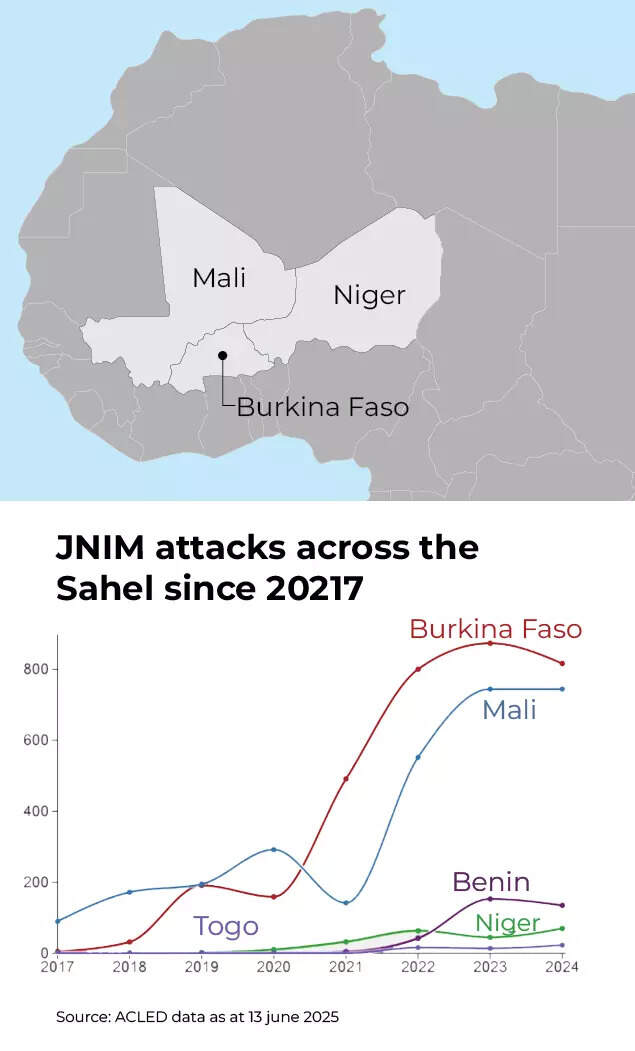

Mali’s crisis is far from confined within its borders. The jihadist networks that thrive there operate seamlessly across the porous frontiers of Burkina Faso, Niger, and Mauritania. JNIM cells coordinate raids with affiliates in southern Algeria and western Niger, while local offshoots pledge loyalty in Ghana and Benin.If Mali falls entirely under JNIM control, it could create a contiguous arc of jihadist influence stretching from the Atlantic coast to the shores of Lake Chad — a vast corridor of instability. This would undermine fragile governments in Ouagadougou and Niamey and destabilize trade routes critical to coastal economies.

Already, neighboring Burkina Faso — also under military rule — faces near-identical conditions. Jihadists control large swathes of its countryside and lay deadly sieges around towns. In Niger, the 2023 coup and subsequent Western withdrawal have created yet another vacuum that militants exploit. A coordinated jihadist offensive could, within a few years, carve a de facto emirate across the Sahel — an outcome that would reverberate well beyond Africa, offering Al-Qaeda an ideological resurgence after years of overshadowing by the Islamic State.

‘Authentic Jihad’

Despite its regional focus, JNIM remains ideologically loyal to al-Qaida’s global leadership. Its propaganda frequently praises Osama bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri, positioning itself as a disciplined standard-bearer of “authentic jihad.” Intelligence reports suggest that Al-Qaeda central, operating from remote hideouts in Afghanistan and Pakistan, views JNIM as its most successful and resilient franchise. Unlike the chaotic Arab uprisings or the implosion of the Islamic State’s caliphate, JNIM’s slow and methodical approach offers a different blueprint: one that wins hearts before annexing territory.Western counterterrorism officials now fear that Mali could serve as a secure platform for transnational operations — training camps, smuggling routes, and cyber propaganda hubs. The vast ungoverned terrain of the Sahel provides both concealment and mobility. Moreover, weak borders and corruption enable the easy movement of fighters and weapons from Libya to Nigeria.

The human cost

For Mali’s 22 million people, the unfolding takeover is not abstract geopolitics but daily survival. Nearly 2 million are internally displaced, and humanitarian corridors have collapsed. Agricultural output has fallen sharply amid conflict-driven displacement and climate stress. Women and children bear the brunt. In areas under jihadist control, strict Islamic codes dictate dress, mobility, and public conduct. Schools teaching secular curricula have been shuttered. Girls’ education has virtually ceased in some provinces. Humanitarian organizations face extortion by both the army and insurgents, forcing them to negotiate their own security.A senior NGO worker in Bamako described the situation bluntly: “We are witnessing the slow-motion Talibanisation of Mali. It’s not an overnight capture but a suffocating encirclement. Every road we take is a gamble.”Meanwhile, the capital remains a bubble insulated by checkpoints and propaganda. State television frequently broadcasts footage of triumphant military parades while avoiding mention of lost territories. The junta’s censorship and jailing of journalists have further blinded the urban middle class to the scale of national collapse.

Religion, power, and survival

Religion in Mali, historically tolerant and syncretic, is being rapidly transformed. JNIM’s doctrinal enforcement is reshaping spiritual life across the countryside. Mosques are repurposed as centers of governance. Friday sermons are monitored for dissent. Social and tribal disputes once settled by local elders are now adjudicated under jihadist sharia.At the same time, the insurgency’s ideological appeal draws selectively on Malian grievances. JNIM frames its rule not as foreign occupation but as a moral alternative to corruption, Western interference, and elite betrayal. This narrative resonates where state institutions have collapsed entirely.Yet, not all accept jihadist dominance. Civilian militias, particularly the Dan Na Ambassagou group among the Dogon community, continue to resist. Their clashes with JNIM — and sometimes with rival ethnic groups — have turned the central regions into a blood-soaked cauldron of revenge killings. Local conflict has fused with global jihad under a devastating logic: in Mali, survival itself is political.

The future of Mali

If JNIM consolidates its control, Mali could become Al-Qaeda’s most durable territorial stronghold since Afghanistan before 2001. Unlike Somalia’s Al-Shabaab, limited by clan dynamics, or Yemen’s AQAP, constrained by war fatigue, JNIM commands a vast hinterland with access to gold, livestock routes, and desert trade networks. That economic base offers strategic depth — a self-sustaining jihadist economy blending taxation, contraband, and protection rackets. Combined with ideological discipline and grassroots integration, JNIM may achieve what Al-Qaeda’s central leadership long sought but failed to maintain elsewhere: a viable Islamic emirate that governs, not just terrorizes.The regional consequences would be immense — from refugee flows toward Europe to the spread of radical networks into West African coastal states long considered stable. For the United States and Europe, whose counterterrorism priorities shifted to Asia and cyber threats, the Sahel risks becoming an unattended wildfire.China, meanwhile, has quietly expanded security cooperation with Sahelian regimes to protect mining interests. Its private security contractors and infrastructure investments will almost certainly clash with jihadist aims, adding a new layer of complexity. The stage is set for an unpredictable multipolar scramble over a failing state — one that jihadists are currently winning through stealth and endurance.

The ‘Day After’: Scenarios for 2026

If the current trends continue, Mali faces two grim scenarios in the coming year.

Scenario A:

The Afghan Model (Total Collapse) The most dramatic scenario is a cascading collapse of the Malian Armed Forces, similar to the Afghan National Army in 2021. If JNIM cuts the final supply lines to Bamako and the Africa Corps decides the situation is untenable, the junta could flee.

Result:

JNIM marches into Bamako. This would be the first time an al-Qaeda affiliate has captured a sovereign capital since the Taliban. It would trigger a massive refugee crisis and likely prompt an immediate intervention by neighboring states (though their capacity is limited).

Scenario B:

The Somali Model (Permanent Attrition) A more likely scenario is that Bamako becomes a “green zone”—a fortress city protected by the Africa Corps and elite FAMa units, while the rest of the country is abandoned to JNIM.

Result:

The government becomes merely the “Mayor of Bamako.” The economy collapses completely, hyperinflation sets in, and the country devolves into a patchwork of warlord fiefdoms. The junta survives, but the state of Mali dies.

Ticking clock

History rarely repeats, but it echoes. The US withdrawal from Kabul in 2021 provided jihadists worldwide with a psychological victory. Mali may soon offer a sequel — not an airlift from an airport, but the quiet absorption of a state into the world’s newest jihadi territory. If that happens, it will not merely be a Malian tragedy. It will redefine the global map of extremism, validate the long-game strategy of Al-Qaeda affiliates, and confront the international community with a haunting question: how many times must a state fail before the world learns to act before the collapse, not after?For Mali’s weary citizens, answers cannot come soon enough. Their homeland — cradle of the great Timbuktu manuscripts, crossroads of African civilization — now balances on a knife’s edge between historical renaissance and irreversible ruin.