If the Olympics is one of the world’s biggest sporting events, its opening ceremony is its crowning glory. The 2024 Paris edition is taking things up more than a few notches. The first Games to have the curtain raiser outside a stadium, it will see almost 100 boats carrying an estimated 10,500 athletes down the Seine. The quays will become spectator stands while the sun reflects off famous Parisian landmarks. And with all eyes on the global fashion capital, everyone is a fashion critic.

Dressing any national contingent for the occasion is a flex. Top designers, luxury houses and sportswear brands vie for the honour. 2024’s lineup of uniform-makers include Ralph Lauren for the United States, Berluti for France, Emporio Armani for Italy, and Lululemon for Canada, among others. For the 117 athletes of Team India, it is Tarun Tahiliani, the New Delhi-based couturier, via Tasva, the premium affordable menswear label launched by him and ABFRL (Aditya Birla Fashion and Retail Ltd.).

India has not had the most shining track record when it comes to dressing up for the ceremony — the team relies on traditional dressing with little designer flair or major crafts showcase. With Tasva taking on a sponsorship role, this edition is the first time that a designer created the ceremonial uniforms.

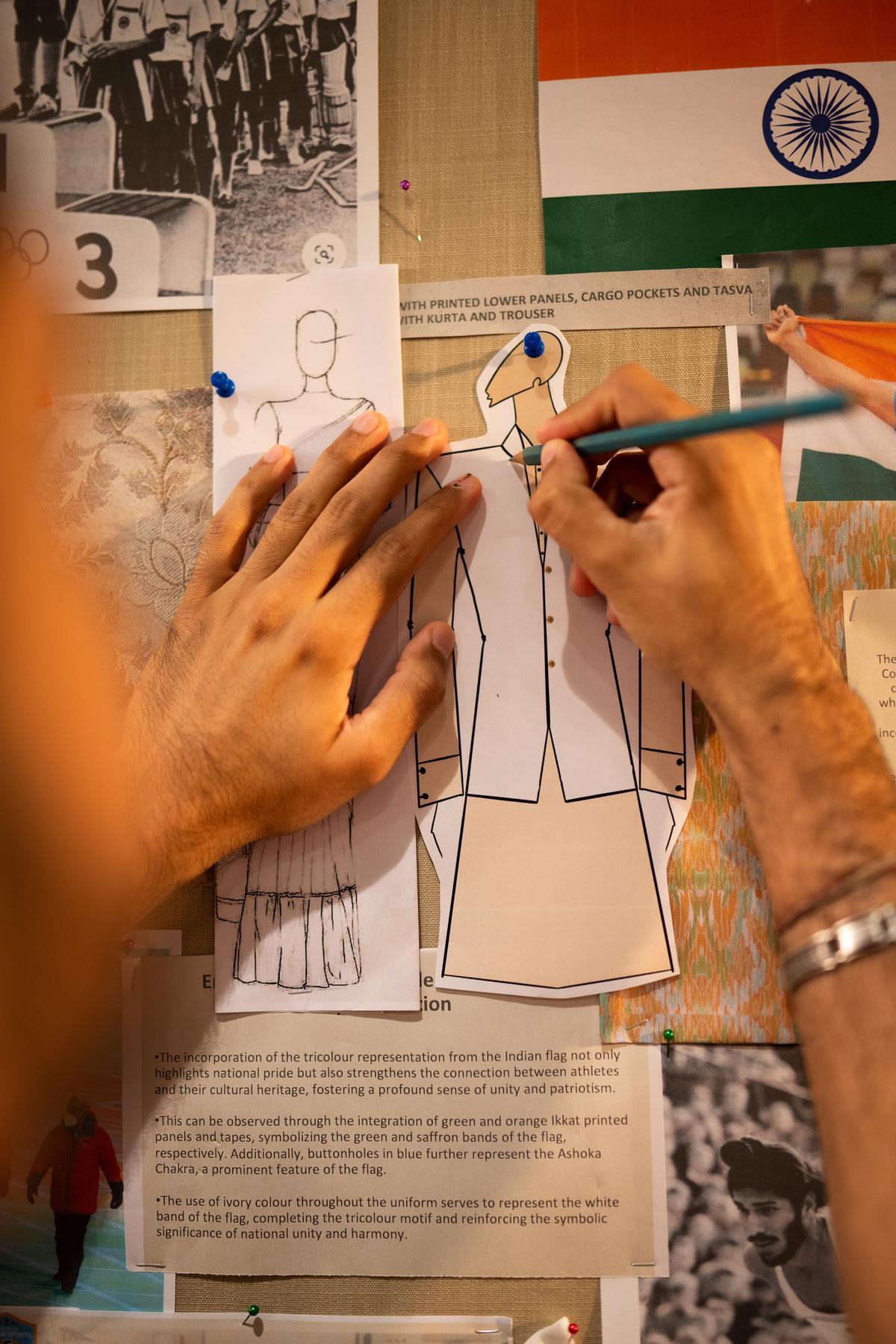

The bandi is the hero silhouette layered over a kurta set.

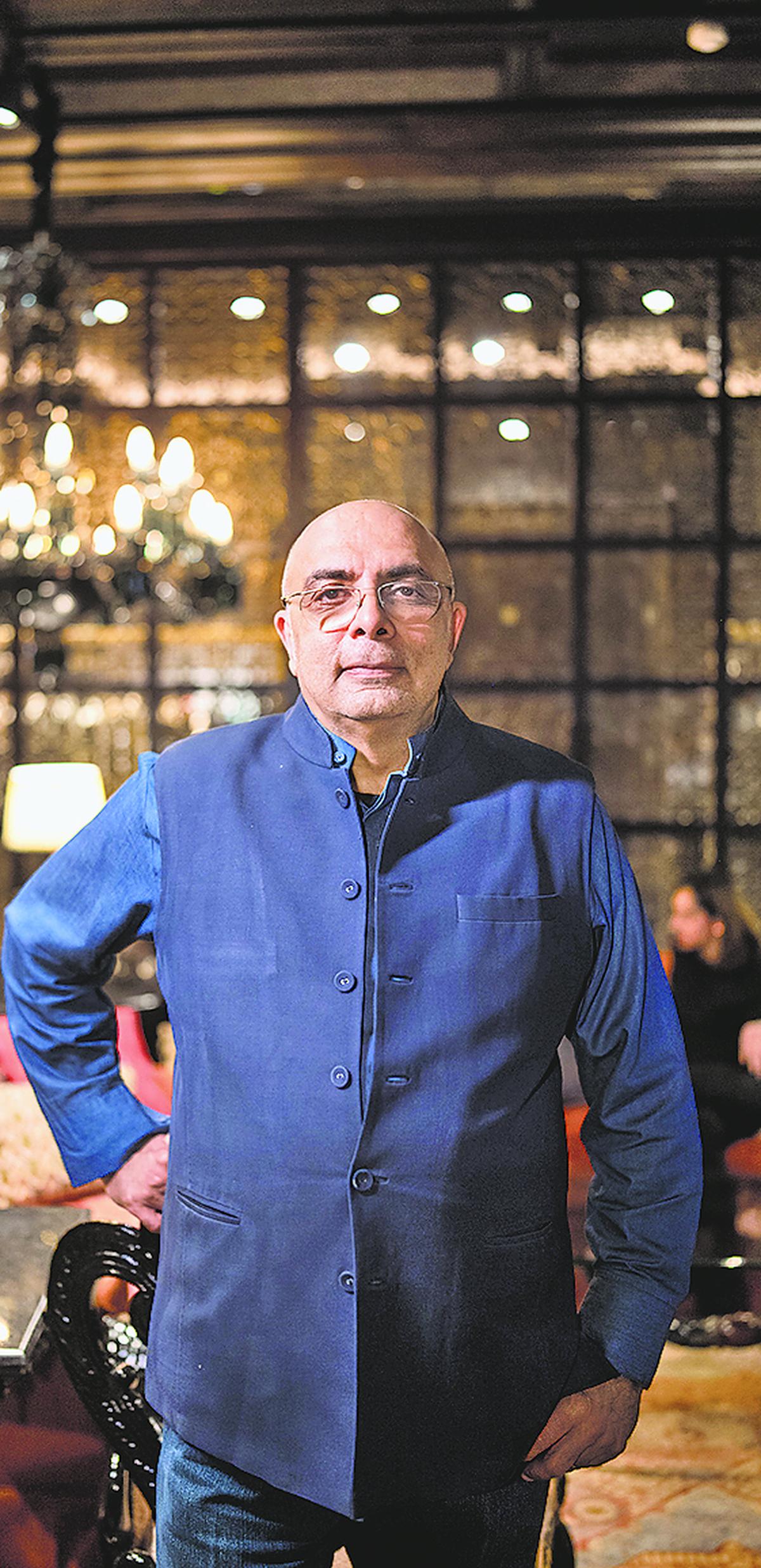

Part of the first generation of Indian fashion, Tahiliani has underpinned his nearly 30-year career with experiments in a distinctive India Modern aesthetic. A master of sculpting and draping, he applies Swarovski crystals and lamé on his luxurious designs with the same flair as brocades, chikankari and zari embroidery. In 2021, as part of a joint venture with ABFRL, he launched Tasva (now with nearly 75 outlets) — offering weavers the kind of supply and price points that wouldn’t be possible had everything been handwoven or hand-embroidered, and giving customers the Tahiliani experience at as less as ₹1,599. It’s not something many designers can boast of.

Designer Tarun Tahiliani

Missed opportunities

Last month, when Mansukh Mandaviya, Minister of Youth Affairs and Sports, unveiled the Olympics official outfits, the designer was in attendance, along with IOA (Indian Olympic Association) president P.T. Usha, hockey players Jarmanpreet Singh and Nilakanta Sharma, and shooter Anjum Moudgil. Expectations were high, but the news did not travel much beyond the event.

At the launch of Team India’s official Olympics uniforms

| Photo Credit:

ANI

Social media was mostly silent, until two weeks later when Team India’s uniforms began to trend on X (formerly Twitter) after a user posted photos from the unveiling. Terms like ‘tacky’ and ‘uninspired’ were used. The images being juxtaposed with Team Mongolia’s uniforms — artfully photographed and styled, as opposed to India’s uniforms that were unimaginatively draped on mannequins — exacerbated the situation.

Since then, similar reactions have mushroomed across platforms. Some posted that the designs gave off an Independence Day school function vibe, while others stated that it was time “the heads realise that investing more time, money, and better resources is a necessity”. Scale is a counter argument to make as to why Mongolia’s uniforms were so intricately crafted. Designers Michel Choigaalaa and Amazonka Choigaalaa only had to dress 32 athletes, and they could afford to spend hours on each uniform — with its ivory silhouettes inspired by the traditional deel (tunic), billowing sleeves, and embroidered vests with the sun, moon, and Gua-Maral (mythical deer from Mongolian folklore).

Mongolia’s intricately crafted uniforms

In the weeks since, Tasva has released new video content and images to showcase the garments, but the criticism has been hard to quell. Sports writer Sharda Ugra notes that while the “clunky presentation” did not make a good first impression for the garments, Tahiliani’s uniforms will be worn IRL in a different setting. “This year’s ceremony will be hosted in the daylight, as the sun doesn’t set till very late in Paris in summer,” she shares. “The athletes will be on boats on the Seine, and next to the flag, the uniforms may look different.” The Indian contingent will wear the same uniforms to the closing and felicitation ceremonies.

Going beyond the blazer

India’s uniforms for the Olympics have shown little evolution over the years. Men tend to wear blazers, bandhgalas or sherwanis, sometimes accompanied with a turban. Women wear saris, almost always with a blazer, which often does little apart from obscuring the rest of the ensemble. During the 2012 Olympics, many women athletes, including tennis player Sania Mirza, walked with their blazers folded over their arms, offering everyone a better view of their bright yellow saris. Even when the uniform for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics switched from sari to a salwar suit, the blazer remained.

Tennis player Sania Mirza and others of the Indian delegation at the opening ceremony of the 2012 London Olympic Games

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

Tasva’s uniforms depart from these norms in many respects, including skipping the blazer. “When we did our research, we saw that prominent international designs were done to coordinate with the colours of their national flags,” says Tahiliani, speaking of the tri-colour inspiration. “We have athletes from around the country, and ivory usually suits everybody.” The bandi became the hero silhouette layered over a kurta set.

The process began in January, and Tahiliani notes there was no specific brief or guidelines from the IOA for the uniform’s design. It was finalised following multiple iterations and feedback sessions; garments were crafted in stages as athletes qualified for various sports. Some qualifications continued well into June, and the Tasva team created a total of 300 uniforms for athletes and accompanying staff. “I did fittings thrice, and I was there for every meeting,” says Tahiliani, responding to criticism that he did not spend enough time on the design and production.

Ugra says that many of the design elements make for a refreshing change, particularly the custom tussar gold brocade sneakers. The digitally printed tri-coloured ikat patterns have polarised opinion, but she observes that it can have a special appeal for its wearers. “The flag is very important to athletes, and they will feel proud to wear the tricolour on their uniforms.”

Custom gold brocade sneakers

Originally, both men and women athletes were meant to wear the same uniform. The sari — a leitmotif in Indian ceremonial uniforms and regarded as a cultural marker — was introduced later, Tahiliani tells me, following a revised mandate from IOA. But as Ugra rightly points out, many athletes don’t know how to drape the sari and first-time wearers may find it daunting on a global stage. “India has so many options for women to wear, be it the mekhela-chador or a salwar suit,” she says. “The aim should be to have well-fitted and comfortable garments.” Tasva offered a solution for any draping issues with pre-pleated saris, a signature design element from Tahiliani’s repertoire.

Not standing on ceremony

Collaborations with designers are not limited to ceremonial purposes, but extend to uniforms of all kinds. Hospitality and aviation sectors — where the staff is expected to look sophisticated — often engage fashion designers. In 2010, Rajesh Pratap Singh, known for his clean, contemporary silhouettes, and make-up artist Ambika Pillai, partnered to create a new look for the cabin crew of Indigo. More recently, Singh designed uniforms for the Akasa Air crew in 2022. Air India’s rebranding last year also reflected in new garments, created by Manish Malhotra.

Rajesh Pratap Singh’s uniform for Akasa Air Crew

Irrespective of the designer, uniforms are a brand entity. “It is important to begin with understanding the client’s vision and the social landscape they interact with,” says designer Raghavendra Rathore, who put the Jodhpuri bandhgala on the fashion map. “Balancing aesthetics with functionality, ensuring a proper fit for a diverse group of wearers, and maintaining high-quality standards are crucial for uniform design.” His eponymous label has created garments for ITC Hotels, Imperial Hotel (Delhi), The Claridges, Umaid Bhawan Palace, and Jio World Convention Centre, as well as a ceremonial uniform for BSF (Border Security Force).

Raghavendra Rathore’s BSF uniforms

The Abraham & Thakore label is known for their engagements with ikat and hand block printing. They have also experimented with handloom uniforms in the past. David Abraham notes, however, that it can be a “completely impractical” choice. “The garments go through rigorous use. How can we expect flight attendants who may wake up at 3 a.m., wash and wear their garments regularly, and use it for at least for 6-12 months, to maintain the garments?” he asks. “Handlooms have beauty and value, but it is ill-advised to use in a space for performance-textiles.”

What many don’t realise is that while a designer tag is attached to such collaborations, what you see is not what you get. Industry insiders who have worked on corporate uniforms agree that though designers are posited as the face and minds behind it, a lot goes on behind the scenes. “There are far more people involved in the design and selection, especially in big, public sector enterprises,” says designer Nimish Shah, whose label Shift created the crew uniforms for Spice Jet in 2017. “It is just not about a designer’s acumen.”

Fashion designers (L-R) David Abraham, Rajesh Pratap Singh, and Raghavendra Rathore

Why are handlooms missing?

In a country known for its weaving and handloom culture that go back centuries — producing handwoven silks and cottons, from Banarasi to Madras checks that have found global renown — the use of digitally printed ikat in this year’s Olympics uniforms seems unimaginative. The buzz around National Handloom Day (August 7) is also giving momentum to people’s criticism of the use of viscose textiles.

Budgets don’t always support the engagement of handloom clusters, and crafts interventions require time and collaborations with craftspeople for distinctive designs. “It’s not a vendor type system where an order is placed and there is an assembly organised production line,” says crafts practitioner and author Meera Goradia. Quick turnabouts — such as, when the IOA decided to ditch the kurta and go with the drape for women athletes — are impossible. While working with “easily available colours, designs that can be produced at scale, or building on fabrics in stock” such as Kutch kala cotton weaves and Banaras jacquards can facilitate faster production, Goradia adds that planning is paramount.

“To make uniforms that are hardy, but also easy and comfortable, all while expressing the brand’s values can be a challenging experience.”David AbrahamOne half of Abraham & Thakore, which has created uniforms for The Oberoi, Taj Group, and Vistara Airlines

Tahiliani says, in the case of the Indian Olympics uniforms, he chose ikat as emblematic of a weaving tradition practised around the country, but opted for digital prints to meet timelines. The choice of viscose was also deliberate. “Cotton would have crushed badly. We used viscose because it is a wood pulp fibre and lets you breathe. It is cooler than silk,” he says. “We had to consider breathability because the athletes would be on a barge, in the heat, for up to five hours.”

Similar criticism has been levelled at airline uniforms in the past. Goradia sees value in using traditional skills, but with logistical consideration. “Using cultural techniques and vocabularies in everyday spaces would not only generate employment, but give visibility and pride to both the maker and the user,” she says. “R&D needs to be done before this can be applied at scale — the quality of the fabrics for durability, dyes, and prints that would be hardy enough to take multiple washes, stains, etc.”

Uniforms: always a point of debate

In the age of social media, presentation becomes paramount for uniforms as much as any fashion collection. It is not surprising that national committees and brands have invested heavily in visual imagery to showcase their ceremonial uniforms. The virality of the Mongolian outfits was also due to the quality of photographs in which these were presented.

The Team India incident has certainly emphasised the need for sport committees to pay greater attention to how designs are presented. But India is not the only team facing criticism for its uniforms. Fans have criticised USA’s opening ceremony blazers — tweeting that they are past their heyday — while Thailand’s outfits were panned for being outdated, to the extent that the country’s prime minister issued a statement defending the uniform. They have since switched to an eye-catching dark blue design with motifs inspired by Ban Chiang pottery.

Thailand’s new uniforms

Tahiliani admits that the presentation, particularly the mannequin drapes, have been weak links but is confident that the uniform will deliver. “We stand by our designs,” he insists. “The team will look great when they take their place in the ceremony, and I will be cheering them on.”

The writer and editor is based in Delhi.